Since the start of the 2005-2006 school year, an initiative backed by the city’s Office of Cultural Affairs known as the Cultural Experience Project has organized free arts-related field trips for Atlanta Public Schools’ students to venues such as the Alliance Theatre and the Center for Civil and Human Rights. The organization aims to send each APS student on one field trip per year. Most recently, high school students visited Georgia Tech’s Ferst Center to see Mark Gindick on Jan. 21.

Before the CEP, students from other districts experienced cultural programs that APS students were missing out on.

“There were lots of kids experiencing trips who weren’t APS students,” said Camille Love, the Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs. “We negotiated with several organizations so that they would provide us with an inventory of seats that would accommodate a class. Once we received a price per seat, we went the corporation and foundation community and said we needed partners.”

Corporate funding makes it possible for students to only gather a permission slip to attend field trips.

“We didn’t want any students to miss these experiences because they couldn’t afford them,” Love said.

Despite the CEP’s intention, art teacher John Brandhorst, Grady’s correspondent with the CEP, said miscommunications lead to under-attended or poorly-organized trips.

“The director of [the Museum of Design Atlanta], for example, will get a call that a CEP trip will come, at 10:00 with 75 people,” Brandhorst said. “She has to hire and pay staff to make this happen. Everybody is there waiting, all dressed up, and maybe the group doesn’t come. Maybe they’re expecting 70, and they get 15. Maybe they get none. They may or may not be told in time to do anything about it.”

Brandhorst cites unreliable transportation as another problem.

“For a trip I was trying to take last year or the year before, I had 200 people taken out of class,” Brandhorst said. “The buses didn’t come because somewhere along the way something didn’t get communicated. We got a message back from the venue, saying ‘why aren’t you here?’ By the time the buses came, the window of the trip was shrinking and shrinking.”

Though Brandhorst usually opens the field trips to the entire school, a majority of the students who attend do so with their visual or performing arts classes. Teachers from other programs rarely devote class time to the trips.

“The CEP program does not cover [substitute teachers],” Brandhorst said. “Non-arts teachers would generally have to miss first, second and third period. [There would be times when] classes don’t have teachers. There’s not a controlled, supervised space for every student. A lot of the arts kids go because if I know where they, I don’t have to hire a sub. If I’m going to go through all the pain of organizing the trips, I want my students to be the ones who benefit.”

While some core teachers, such as literature teacher Mario Herrera and AP History teacher Sara Looman, schedule trips for their classes, others oppose the absence. Economics teacher Nadia Goodvin, for example, has a strict policy regarding absences, and only allows students to attend trips if they notify her in advance and have a satisfactory grade in her class.

Sara Looman said for both students and teachers, the decision of whether or not to attend a field trip entails a cost-benefit analysis.

“Anytime we’re not sitting in a desk, doing productive work, there’s this idea that it’s [a waste of time],” Looman said. “At a very basic level, you learn how to behave in the world, how to interact with docents or sit appropriately in a concert. That kind of cultural exposure is important.”

This mindset, coupled with a robust testing schedule, leads a small percentage of Grady’s population to take part in the field trips.

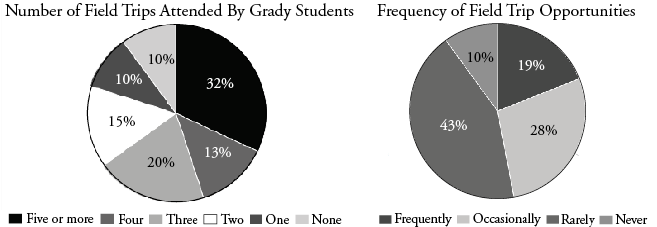

A poll of 150 students conducted by the Southerner found that 32 percent of students have never attended a field trip while at Grady. A further 53 percent either rarely or never receive information about field trip opportunities. While the majority of students have embarked on trips, quite a few wrote on their survey slips that they often hear about field trip opportunities but choose not to attend because they feel that they cannot afford to miss class.

As the Southerner found in a 2015 study, standardized tests consume approximately 20 percent of instructional time. This influx of testing challenges the CEP’s stated goal of providing one field trip per year for each APS student. The CEP cannot schedule field trips on days with standardized tests. As a result, each year’s high school trips are often condensed into a short period of time.

Typically, each grade level in the school system attends one CEP trip per year. To counteract the scheduling woes brought about by standardized testing and block scheduling in high schools, the CEP provides trips throughout the year that are open to all students.

“Instead of there being a single experience, high schools get a menu of experiences,” Love said.

Brandhorst expressed concern, however, that students often attend the trips for superficial reasons.

“[Are field trips] just a chance to get out of school?” Brandhorst said. “How much impact are they getting for the level of investment that goes into the program?”

Love, however, cited the success of the CEP program as an indication of its worth.

“We hope that children who have been exposed to arts and culture will be patrons in the future and look upon cultural institutions as welcoming places,” Love said.