In 2011, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation unveiled its findings that teachers in nearly 80 percent of Atlanta Public Schools schools doctored answer sheets on state-mandated tests to boost scores. APS garnered national attention for the scandal.

Just as perpetrators received their sentences this past spring, two Grady teachers were accused of cheating on a state-mandated teacher-assessment test, called the Student Learning Objectives, and a district-mandated final exam.

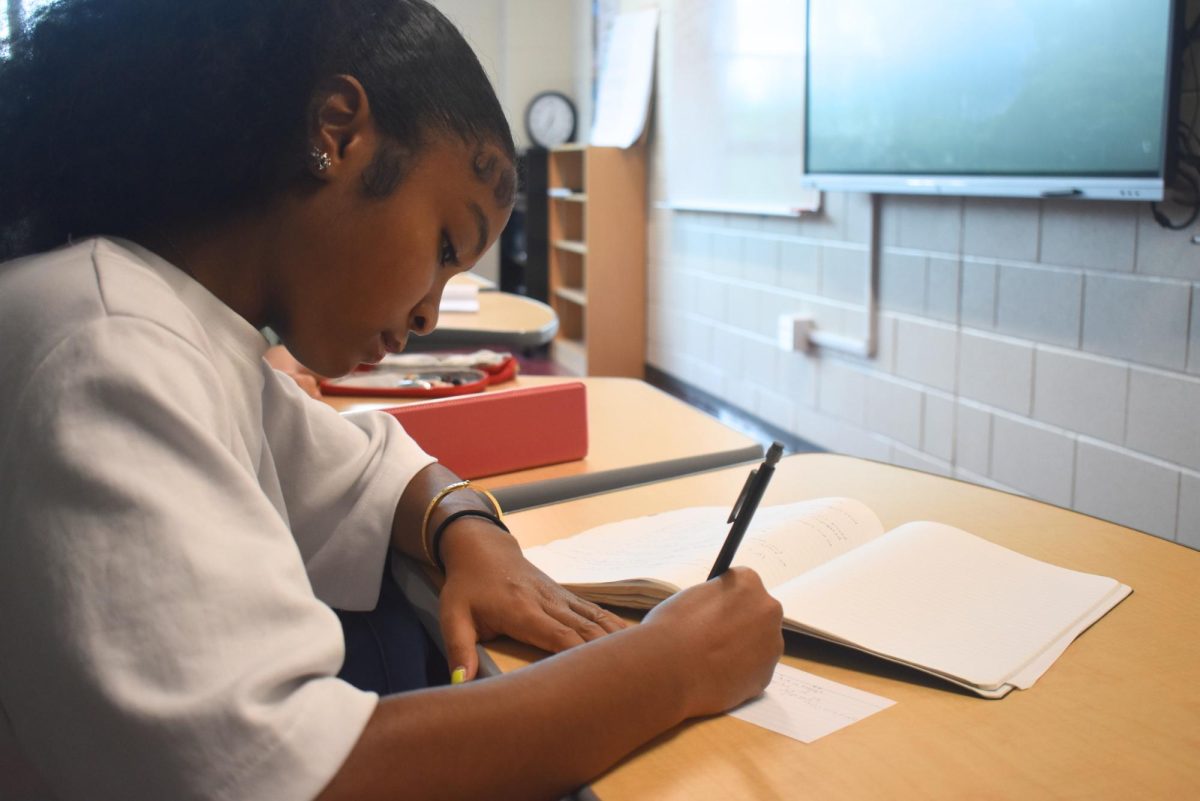

The cheating occurred in a school that has become increasingly skeptical of standardized tests as an effective measure of student knowledge and teacher ability.

Students and teachers said the event indicated an oversaturation of testing in the classroom. Many questioned the validity of the test rather than the potential ethics violation.

On May 20, a teacher filed a complaint with Principal Timothy Guiney alleging that gym teacher Harlen Graham reviewed questions identical to those of the recreational games SLO before taking the test. Six days later, two students filed a complaint alleging that biology teacher David Olorunfemi gave his students district-mandated final exam questions in a study guide before taking the actual exam.

APS investigated the cases over the summer, and district reports concluded that both teachers were guilty of unethical behavior. Neither returned for the 2015 school year.

The tests put pressure on teachers and left room for cheating because teachers administered and graded their own tests.

“What [the SLO] does is measure student growth over time, and it is tied to teacher evaluations, so that can be a factor that causes stress,” Guiney said. “[But teachers] have to make sure they are remaining ethical at all times; the stress can- not be an excuse for violating ethical standards.”

According the report, Graham read SLO test questions and answers aloud to his recreational games classes — under the guise of test practice — the period be- fore the test. Graham denied asking the questions verbatim and giving answer choices, but multiple students also told investigators that Graham failed to create an environment appropriate for testing by allowing students to use their cellphones and share answers during the test. Graham declined to comment.

Senior Gracie Griffith, an editor on The Southerner staff, who was on the girl’s basketball team when Graham coached, said that Graham will be greatly missed by the community.

“I remember him as someone who wanted the best for his students and was really caring about their academic and extracurricular interests,” Griffith said. “[He] was just a really nice, friendly person — someone really good to talk to.”

In Olorunfemi’s case, students received questions in advance of a new test that APS biology teachers must administer, a consequence of state mandates that forced APS to construct its own summative assessment since the Georgia Milestones version wouldn’t be ready in time for APS teacher evaluation deadlines. Olorunfemi declined to comment.

“I have taught with [Olorunfemi] for 20 years, and I have seen how hard he works, how much he helps people,” science teacher Gabangaye Gcabashe said. “He used to be the go- to guy for people who were failing the [Georgia Graduation Test], and he would work with them in the afternoons. Most of them would then take the exam and pass.”

Testing coordinator Raymond Dawson said teachers were responsible for creating an environment conducive to testing and following ethical guidelines. Whereas SLOs last year required teachers to hand out paper test documents, SLOs this year are administered online.

“The level of security [this year] is phenomenal,” Dawson said.

Additionally, Dawson said the online tests eliminate the possibility of teachers using stray copies of the tests to prepare students before the actual test.

A system gone awry

Despite the improvements, the incidents reveal possible complications that may arise from using tests as instruments to evaluate teacher performance.

“The whole purpose of the SLO is to allow the teacher to demonstrate their effectiveness for student growth,” said Michele Purvis, a DOE program manager of the division of teacher and leader effectiveness.

SLOs were created in conjunction with the Teacher Keys Effectiveness System. Through TKES, 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation is based on student growth measured by the Milestones and SLOs. Georgia adopted TKES as part of its Race to the Top plan, which was a $4.35 grant billion grant from the U.S. Department of Education “designed to spur systemic reform and embrace innovative approaches to teaching and learning in America’s schools.” Race to the Top required participating states to measure student achievement and teacher effectiveness through assessments for nearly every course.

Guiney said Georgia’s attempt to secure Race to the Top dollars ushered in more frequent and impactful tests to measure student growth.

“There were no growth measures for non-core classes and things like that,” Guiney said reminiscing of his time as a Clayton County teacher. “All that has come about in the last three years, and some of those things have come in as a result of Race to the Top.”

Art teacher John Brandhorst said the SLOs reduce education to a set of “ovals” and data points and that the obsession with data in today’s education prevents all students from living fulfilling lives.

“I am not a widget,” Brandhorst said. “We are not cattle. The measurements are crude abstractions of the task actually at hand.”

Purvis said the DOE has received “overwhelmingly positive feedback” from teachers and districts using SLOs and that the tests raised the value of teachers from previously untested subjects by allowing them to analyze student growth and communicate that growth through standardized scores.

Testing validity

While the SLOs do offer scores, many question whether the scores are needed or valid as measurements of teaching ability.

“It doesn’t make much sense to give a personal fitness class a standardized test,” alumnus Ben Simonds-Malamud said. Simonds- Malamud was one of Graham’s recreational students last year. “It’s a class about working out.”

Purvis disagrees.

“Everyone that teaches a child needs to be held to a consistent expectation,” Purvis said.

The validity of a SLO result also predicates on the assumption that students take the exam seriously.

Gcabashe said many students don’t take SLOs seriously because they are not tied to a student grade.

“Nobody takes that thing seriously,” Gcabashe said. “I’ve seen people finish that thing in five minutes.”

Brandhorst said students in his sculpture class finished the test before he handed out the questions. He said he cannot give students a compelling reason to care about SLOs, and, as a result, they use the test to reward teachers they like personally.

“There are students who use the SLOs as a vindictive or rewarding device since they know it doesn’t affect them, and they know it does affect the teacher,” Brandhorst said.

Craig Harper, Director of Communications at the Professional Association of Georgia Educators teachers union said SLOs hold teachers accountable for too much. Even if students take the exam seriously, student growth is reliant on many factors outside of what the teacher did in the classroom. The motivation and parental support a student has can both affect a stu- dent’s score on a SLO and, consequently, the teacher’s evaluation.

“So many other factors go into an individual student’s individual achievement beyond what the teacher did in the classroom,” Harper said.

Science teacher Nikolai Curtis said that in his experience, high- performing students with a sound educational foundation fair better on SLOs. Teachers who teach AP classes are, therefore, much more likely to be evaluated favorably through SLOs than teachers who teach primarily on-level classes.

“I think there are a lot of discrepancies that aren’t addressed appropriately to allow us to give an accurate measurement between classes,” Curtis said.

Apples to oranges

Harper also said the fact that SLOs are developed locally by districts brings their validity into question, since test-writing itself is a specialized field. Whereas the Milestones test is produced by McGraw- Hill, SLOs are often produced by teachers of the course in the district. With 181 different school districts in Georgia, teachers wind up ad- ministering 181 different tests for the same course. The tests are different but each is weighted in a teacher’s evaluation equally.

“It is a lot to ask those teachers to develop their own test, and they are based on Georgia standards, but every district was able to advocate for fidelity to develop their own SLOs, so there’s a lot of variety among districts about what are on those tests versus a Georgia Mile- stone,” Harper said. “Teachers who we’ve talked to who are evaluated by the standardized test feel that the SLOs are not at the same level of validity and reliability because they are developed locally.”

Purvis said SLOs developed in line with “local education agency- identified growth measures” give districts more autonomy in determining teacher effectiveness.

“SLOs are designed to be as close to instruction in the class- room as possible and need to be reflective of the district expectations,” Purvis said.

Brandhorst said comparing SLOs across districts is like comparing “apples to oranges.” “The SLO is based on standards, but across the state, there is not a standard curriculum,” Brand- horst said. “The SLO will reflect the political nature of that locality. That inconsistency makes it a rather invalid measure.”

Harper worries that tests written by teachers are ultimately less effective than Milestones at assessing student knowledge. Brandhorst said he has seen errors in multiple SLO tests.

“Test writing is a pretty technical field, and it can be really easy to in- tend to ask a question with a specific answer and then not be as clear as you think,” Craig said.

Purvis said the state has put safeguards in place to ensure each SLO is rigorous and reflective of student growth.

Before developing the SLO, districts complete a “content alignment form” to identify the standards being assessed, “the cognitive demand of those standards and the instructional emphasis for the course.”

Districts also complete a table of specifications which is submitted to the DOE. The table of specifications indicates the alignment of the assessment with what is being taught in the course. Through the table of specification, the district indicates the type of assessment. Finally, the district submits a criteria table which reviews the assessment items, formatting, administration and results.

Teacher involvement

Regardless of the safeguards, the teacher’s direct involvement in the test writing process means that some teachers have complete knowledge of the SLOs’ content whereas teachers who were not involved in the SLO development process or who are evaluated by Milestones have no knowledge of the questions on the test their students are taking.

“It can seem disproportionate that some people know exactly how the tests were developed and what content is going to be covered and others don’t,” Harper said.

Knowledge of the specific questions or content on the test can in- advertently impact what and how the teacher teaches.

“It gives teachers motivation to change their teaching to match exactly what is going to be on the test,” Harper said.

In Graham’s case, the local development of SLOs possibly blind-sided him about the content of the test, one student in his class said. While there are standards associated with recreational games, there is no defined curriculum for the class.

“In the end, he had no control over what the test was like going to ask us as students, so he had almost no way to prepare us for it,” said Junior Bailey Damiani, who was in Graham’s recreational games class last year.

While Georgia only implemented its Race to the Top plan in 2010, there is already a shift at the state and federal level away from testing. This school year, under a new flexibility option, the Department of Education allows districts to evaluate teachers with only two growth measures. This means teachers evaluated with a Milestone only have to administer one SLO. A teacher who teaches three courses not tested by the Milestones can be evaluated with two SLOs.

In October, President Barack Obama released a Testing Action Plan calling for less testing. Georgia Schools Superintendent Richard Woods said he supported the action plan and would seek to provide relief from over-testing.

“It’s interesting to watch the pendulum swing, with different presidents, with different superintendents — to watch the priorities come and go,” Brandhorst said.