By Will Taft and Harrison Wilco

Georgia voters will decide next November whether to amend Georgia’s constitution and enable the creation of an “Opportunity School District.” The proposed OSD amendment, which allows for state-led intervention into “chronically failing” schools (currently defined as those schools with College and Career Ready Performance Index scores below 60 for three consecutive years), already passed with the two-thirds majority required for a constitutional amendment in both chambers of the Georgia General Assembly.

Senate Bill 133 outlines how the government would utilize the OSD amendment if it is approved by Georgia voters. The governor would appoint a state OSD superintendent who would have sole discretion in selecting up to 20 qualifying schools each year. These schools would then be eligible to be included in the OSD. In any given year, the superintendent could control no more than 100 schools. SB 133 includes four ways the superintendent could choose to intervene with a “chronically failing school.” The superintendent can directly manage the school, allow the local school board to maintain control of the school while directing changes, reconstitute the school as an OSD charter school with a charter approved by the State Charter School Commission, or close the school.

“OSD would authorize the state to step in to help rejuvenate failing public schools and rescue children languishing in them,” said Gov. Nathan Deal, who proposed the OSD in his state of the state address.

With 29 schools classified as “chronically failing” — the most out of any district in the state– APS could be drastically impacted by the OSD amendment.

“Atlanta Public Schools is representative of schools throughout our whole state in many ways,” said Rep. Beth Beskin, R-Atlanta. In 2011, Gov. Nathan Deal appointed Beskin as one of two liaisons to APS while it was on accredited probation with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. During her time working with APS, Beskin noted many issues that she believed needed to be addressed.

“I believe there are a lot of educational failures in our state,” Beskin said. “The status quo has been in place for a long time, and these failures have occurred and persisted under the system we have now. So I believe something has to change.”

Not all Georgia lawmakers supported the legislation; a majority of Democrats opposed the amendment and instead backed a system to give grants to impoverished school districts for wraparound services.

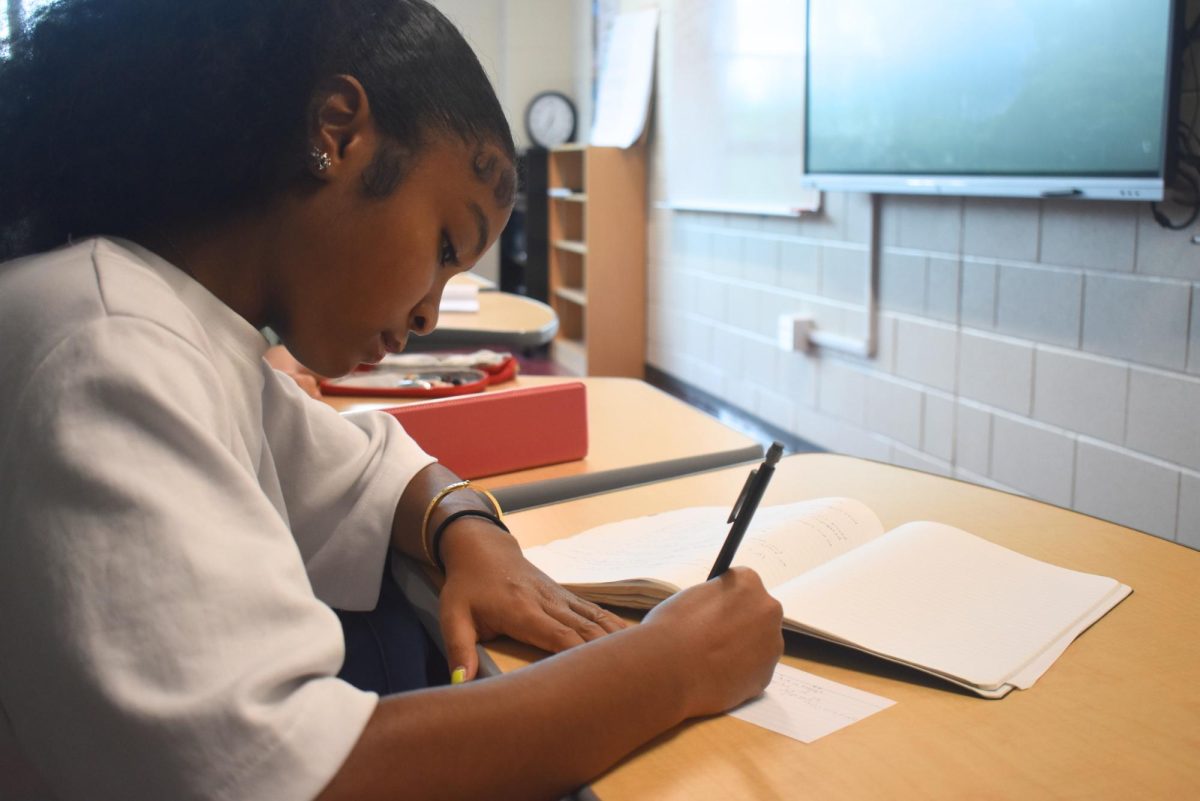

“A child who is hungry is going to have more difficulty than a child who is well fed,” said Sen. Vincent Fort, D-District 39. “There are a lot of children who may not get another meal after that free [school] lunch until the next morning’s free [school] breakfast. You are going to have to provide services to get those kids dinner. Those are the kind of things that are needed.”

Fort co-sponsored Senate Bill 124, Unlocking the Promise Community Schools Act, with a group of Senate Democrats. This legislation aimed to create solution geared more toward providing children living in poverty with extra services. The bill did not reach a vote in the Senate.

Deal’s backing played a key role in the amount of support the OSD amendment garnered in the Republican Party.

“Through the recommendation of the Governor for the Opportunity School District, and through serving on the [Education] Committee and listening to the testimony in committee meetings, I supported the Opportunity School District and voted in favor of it,” Beskin told the Southerner.

Many Democrats, however, believe OSD misses the mark by failing to consider the role poverty plays in causing school struggle.

“OSD is a flawed proposition from start to finish,” said Sen. Nan Orrock, D-District 36. “If you want to turn things around for students that come from impoverished backgrounds you do it with an enrichment of the services that are provided in the school setting.”

Orrock also criticized the OSD amendment for lacking accountability to local taxpayers. Three percent of local funds previously used in the local school system would be redirected to fund OSD.

“It’s a scheme that’s not going to work,” Orrock told the Southerner. “One of the problems first of all is to have a school district that has no accountability to parents…There is no place for input for the community whose tax dollars are being taken by the Governor to fund this.”

Orrock said that she fears OSD will allow corporations to encroach into the public education sphere. One of the enforcement mechanisms available to the OSD superintendent is turning the failing school into a state charter school. Once the school is a charter school, the superintendent and State Charter School Commission can outsource school services to education companies seeking profit.

“That is a very direct way in which the money is lined up in the pockets of private companies,” Orrock said.

According to Orrock, OSD is part of a larger Republican effort to cut funding for education and control schools.

“Their efforts have been very consistent for some years to take over public schools and reduce the voice of educators in the decision–making,” Orrock said.

Republicans, argue the contrary, stating that Deal’s administration has put education funding in the forefront. According to the Georgia Policy and Budget Institute, Deal’s 2016 budget gives a higher percentage of the state budget to schools than in past years. The $8.49 billion slated for public schools in the budget, however, still falls $470 million short of the amount determined by the state’s funding formula.

Orrock, while not supportive of OSD, said she thinks Georgia voters will pass the amendment, citing the likely influx of “right-wing dollars” in an advertising campaign and the “vanilla” language on the ballot.

In 2016, the ballot for Georgia voters will read: “Shall the Constitution of Georgia be amended to allow the state to intervene in chronically failing public schools in order to improve student performance?”

Opponents of the amendments do not think the ballot conveys the true consequence of OSD.

“The amendment itself is overly broad and will give a false impression to voters as to what exactly it will do,” education lobbyist and Grady parent Janet Kishbaugh said. “The referendum [question] is definitely not representative of what will happen if the amendment passes.”