After quitting her job as coordinator of teen programs at the High Museum, a short run of what she deems “bogus part-time jobs”–including a stint at a salt factory–was a necessary evil for Beth Malone, co-founder of Dashboard Co-op.

“It was pretty brave, and pretty dumb—my mom was really mad at me,” Malone said of her decision to leave the High. “[But I felt like] there was a small window of opportunity, and I had to jump ship.”

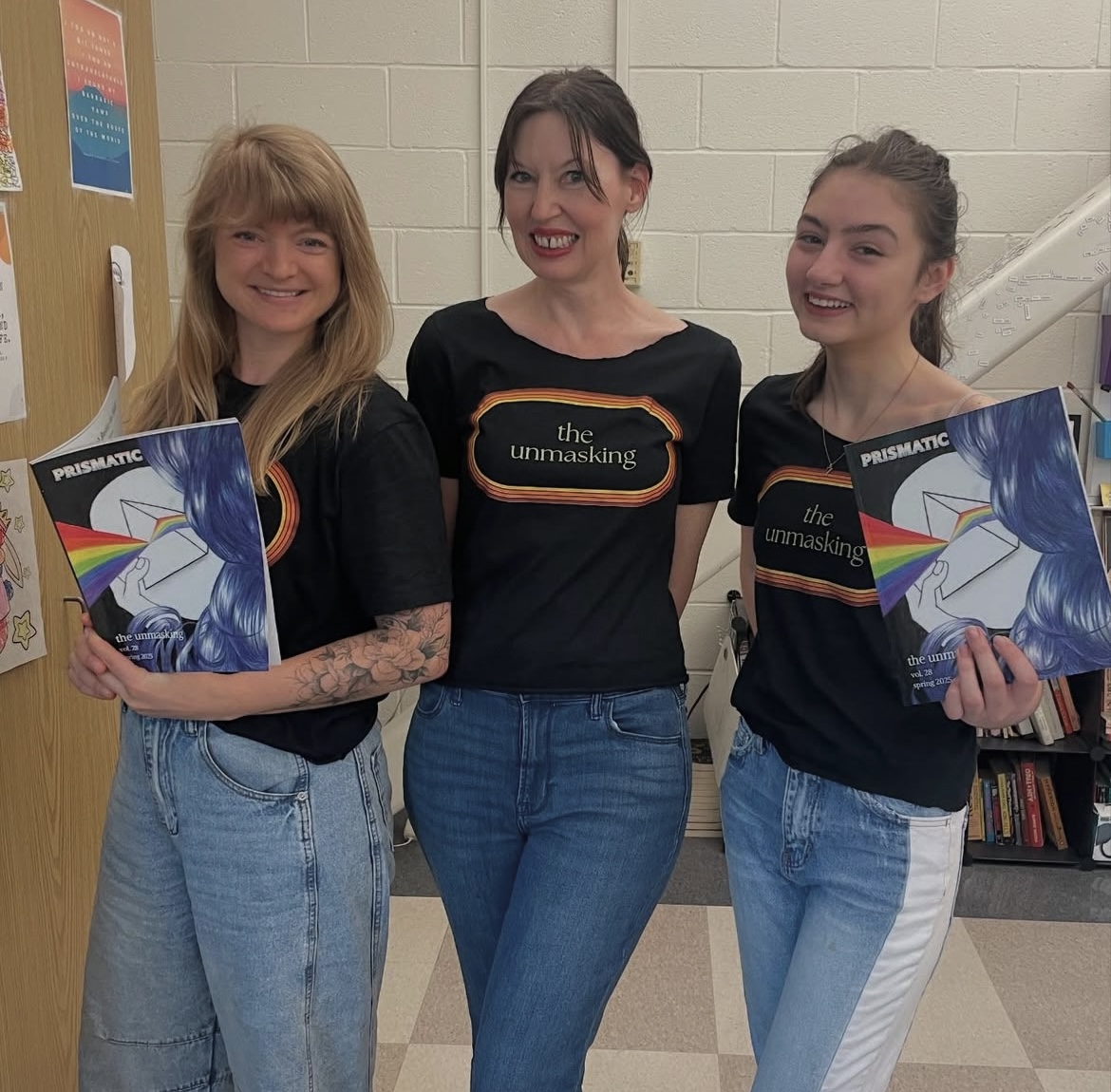

Dashboard Co-op, a nonprofit which Malone started five years ago with her best friend Courtney Hammond, began with a simple goal: to provide Atlanta artists with more ways to showcase their artwork.

“At the time, Courtney and I were really broke so we started finding vacant spaces that people would let us use for free,” Malone said. “We just started producing art shows … around town.”

As Dashboard grew, Malone began to notice a snowball effect in the areas surrounding past exhibitions.

“We realized that other people were moving into the properties we were using and turning them into permanent gallery spaces, restaurants, dance studios or newspaper offices–all sorts of stuff,” Malone said. “We started having this community revitalization component that started to improve neighborhoods. Now it’s kind of our mission to connect artists with space, with the idea that this will improve communities.”

Dashboard now sits at the forefront of Atlanta’s art community. Every year, about a hundred artists apply to present their work at Dashboard exhibits.

“Sometimes we have shows with a theme, and sometimes we don’t,” Malone said. “Sometimes we say ‘make the craziest thing that you want to make.’ We [also] require that artists tell us what they want to make before they go into a space.”

Dashboard’s current exhibition, entitled Dialogue: Conflict/Resolution, deals directly with contemporary racial tension between policemen and black citizens. The show, which is free to the public, closes March 20. The exhibition is on view at Dashboard’s North and Mid galleries, located at 31 and 33 North Ave.

“We very quickly put [Dialogue] together with the idea that using voice and language is a way to combat prejudices and also to react to conflicts and acknowledge conflicts,” Malone said. “We invited six artists to create works or to present prior works using this idea of language and how it can do something with conflict resolution.”

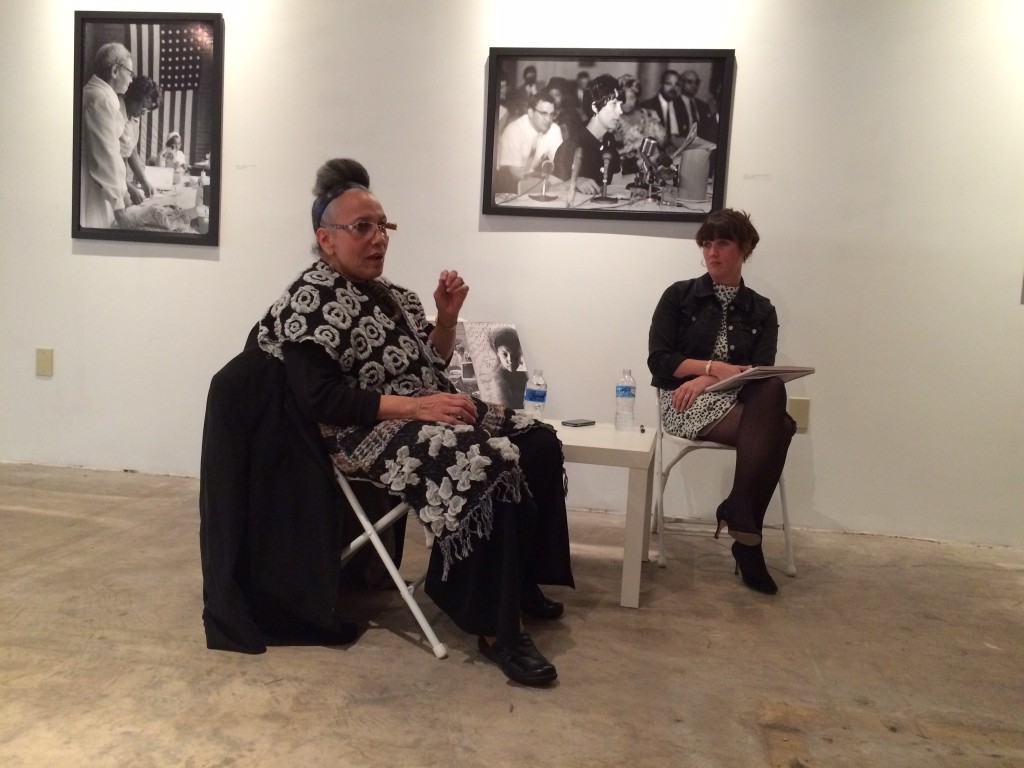

One of these artists is Dr. Doris A. Derby, a documentary photographer and educator, who exhibited photographs she took during the civil rights movement.

“By junior high school, I had decided that I needed to document the history and culture of African-American people,” Derby said. “I already had been doing it through the photography but not seriously. I started … going to various cultural events as a participant as well as an observer.”

When Derby joined a group called Southern Media, Inc., in Mississippi, she officially began documenting civil rights activities.

Her photographs, which balance both artistic and photojournalistic elements, reveal conflicts that ordinary African-Americans faced daily.

“The photographs [show] dialogue dealing with resolution of conflict in a very broad sense,” Derby said. “My photographs reflect ways in which black people in their own communities, through self-help, dealt with the conflict to improve their lives.”

Many of Derby’s photographs depict women participating in the civil rights movement.

“I have one photograph [of] a woman who is teaching adults,” Derby said. “That’s something that didn’t happen very often, especially in areas that were predominantly black. … [Other photographs depict] hearings in front of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.”

Derby said that activists formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s official Democratic Party.

“[Mississippian Democrats] didn’t want us to vote, run for office or participate in [government] in any way,” Derby said. “There were hearings about this whole issue concerning which delegation would be the legitimate delegation.”

Though Derby took her photographs well before Michael Brown’s death captured the nation’s attention, she said that her work echoes a similar sentiment.

“[At the time, Derby] really didn’t get as much attention as she should’ve,” Malone said. “Now, in her older age, she’s been collected by the High Museum, and we’re trying to do as much as we can to bring her to the forefront of the conversation about the civil rights movement.”

Dialogue: Conflict/Resolution’s other pieces range from performance art to video installations.

Michi Meko, an Alabama-based artist, created a sound installation in which garbled voices emit from kettles. His piece, entitled “Pots and Kettles,” plays with the idiom “the pot calling the kettle black” to respond to race issues.

Meko spent the better part of two days recording the sounds, which vary from responses to news stories to speeches from 1960s political figures and the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, to a recording of the correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Banneker.

“[The Jefferson-Banneker letter] gets lost in all of the conversation, which is kind of what I wanted to happen,” Meko said. “… There’s a point in the recording where everything just runs together and it’s all loud, and I think the conversation of race is kind of like that. … There’s so much chatter that you just give up.”

A mobile public art piece caps off the exhibit.

“We have the gallery, but we also have a cop car that one of the artists got from Texas,” Malone said. “It will move around to different locations in Atlanta during the exhibition. The cool thing about the car is that it has the entire grand jury testimony from the Michael Brown case written on the outside. It’s provocative and interesting, and I’m kind of worried that we’re going to get fined, but we’ll see what happens.”