By Max Rafferty and Anders Russell

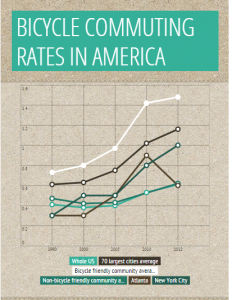

Commuting by bicycle is a rapidly growing trend throughout America. From 2000 to 2012, the number of bicycle commuters nationwide increased 61 percent and a whopping 85 percent in the 70 largest cities, the League of American Cyclists reports.

Mayor Kasim Reed wants Atlanta to be a top 10 cycling community by 2016. According to the census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Atlanta has only a 0.6 percent bicycle commuting rate, which is about half of the 1.16 percent average of the largest American cities. The city has a measly 45.2 miles of bike lanes (New York has 170), one of the primary investments that encourage cycling in cities. The motivation, however, is certainly there. Sixty percent of Atlantans want to ride bikes but don’t feel safe doing so on the city’s congested streets. In order to achieve his goals, Reed’s administration has implemented the Connect Atlanta plan, which aims to improve the transportation system in general, including making the city more bicycle friendly.

There are three common methods of improving urban cycling. Creating bike only lanes is the most common. Bike lanes are a side section of the road set off only by paint. Meanwhile, a cycle track features some type of barrier between driver and cyclist, whether it’s a curb or a plastic divider. Sharrows, the commonly seen double arrowhead over a silhouetted cyclist, are the least obtrusive. Atlanta’s new transport plan calls for all three.

Following the success of the BeltLine’s Eastside trail, pro-cycling initiatives are taking off. In fact, since the introduction of the BeltLine project the private sector has invested over $1 billion in the surrounding area. A survey from Global Strategy found that four out of five people aged 18 to 34 prefer to live in a city which doesn’t require a car to get around, and bike lanes are a key component of this requirement.

The BeltLine also helps businesses along new walking and cycling paths, through newly acquired foot traffic. From the rebranding of the “Murder Kroger to “the BeltLine Kroger” to improved business at Mediterranean Grill, the BeltLine has had a major impact on its surrounding areas.

Based on the success of these programs, the new Connect Atlanta plan calls for $300,000 for the improvement of bicycle infrastructure, including bike lanes and cycle tracks on Peachtree, bike lanes on Auburn and Edgewood avenues and sharrows on Decatur Street, in addition to an extension of the 10th Street cycle track in front of Grady.

In order to best determine the placement of new lanes, the city has relied on the Georgia Tech-developed Cycle Atlanta app, which tracks riders’ commutes in order to determine the best places for lanes to be built. The city has also looked at crash statistics. For example, Peachtree has more bike crashes than almost any other street, but the addition of bike lanes and cycle tracks should change that.

However, some people think the new changes won’t go quite far enough. People park in bike lanes illegally all the time, and the city even allows set up crews to use the lanes legally for events such as Music Midtown.

Atlanta may not be the most bike-friendly of cities, but it is certainly pushing for change. In the words of Mayor Reed, “[The Connect Atlanta Plan] supports my vision for complete streets that are designed for all citizens and modes of transportation.”