During the spring of 2010, the Grady boys soccer team played a game against Druid Hills High School that would determine whether the team advanced to the state playoffs. Guarding Grady’s goal was senior Lee Lowery III, who had become the starting goalie in his first season on the team.

“For them to go to the playoffs, he had to make this really, really big save,” said senior Perri Bonner, who was a freshman on the girls soccer team at the time. “And he did.”

On Monday, Nov. 12, Lowery, a junior at Georgia State University, was shot and killed outside the Ford Factory Lofts on Ponce de Leon Avenue, just one mile from Grady. According to the incident report filed by the Atlanta Police Department, Lowery was shot a single time, around 5 p.m., and died of his injuries later that evening at Grady Hospital. Antonio Johnson was arrested and charged with Lowery’s murder on Dec. 24, according to CBS News.

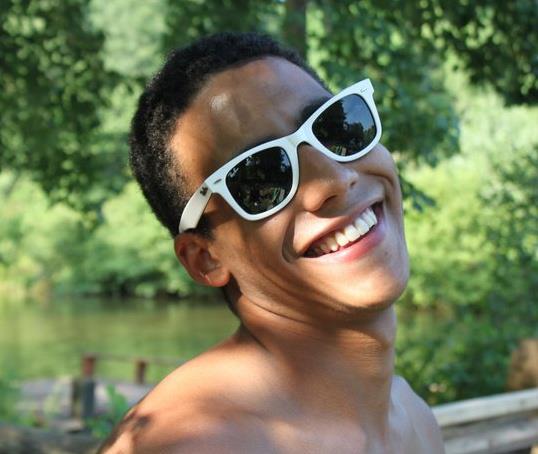

During his time at Grady, Lowery was known for his outgoing personality, his love for spending time with his friends and especially his smile.

“He had an infectious smile that would light up any room and change anyone’s disposition,” said Program for Exceptional Children teacher Mecca Handy, who was Lowery’s homeroom advisor for four years. “Even if he were in trouble, he’d smile his way out of it; at least he thought he would.”

Allison Webb, Lowery’s mother, was 23 when her son was born. She said she felt they had grown up together.

“I get a lot of strength from Lee,” she said. “As I raised him, I learned a lot from Lee. I admired his strength, I admired him being so self-assured, his convictions in helping people.”

Kyle Campis, class of 2011 and currently a sophomore at the University of West Georgia, first met Lowery when they were students at Inman Middle School. The two became closer during high school, when they played soccer together during Lowery’s senior year and hung out after school and on weekends with a group of boys Campis called their “crew.” Campis remembers Lowery had a gift for inventing nicknames that stuck.

“He’d have so much fun calling people names,” Campis said. “We’d hear it so much that we’d start calling each other by these names. Lee’d call me KC and the Sunshine Band. … [His nickname] was Leelee.”

Before his senior year, Lowery mostly played sports for fun with his friends although he was also on a club soccer team. Campis said Lowery, an all-around good athlete, had a special ability to excel at games they invented for fun. After seeing his talent, Lowery’s friends encouraged him to try out for the starting keeper position on the Grady soccer team during his senior year. At first, worried about the pressure of competing against another senior who had been playing for Grady for three years, Lowery declined. He changed his mind, however, and became one of the best goalies Grady has had in years, Campis said.

“That shows a lot about who he was—not playing a lot of soccer but just [having] commitment and being who he was,” Campis said. “He was strong enough to put enough heart and effort into something that he would really care for and enjoy.”

Bonner also got to know Lowery through Grady soccer, as the girls and boys teams shared buses to games. During the summer of 2010, Bonner was walking through Virginia-Highland alone on a hot day. Lowery happened to drive by and offered her a ride, even though they were headed in different directions.

“There are probably like three people I know that I’ve ever met that have been completely genuine, and he’s probably number one,” Bonner said.

Webb said one of her strongest memories of Lowery is his love for singing–and his inability to stay on key.

“Not only was he off key, he had all the wrong lyrics,” Webb said. “When he was really young, he’d always sing ‘I Believe I Can Fly.’ He was always doing things like that, turning something that might not be funny into something funny.”

Even after Lowery graduated from Grady in 2010, he kept in close contact with his high school friends. Sam Altman met Lowery while in kindergarten at Morningside Elementary School. After high school, Altman moved to Athens and Lowery remained in Atlanta, but the two still saw each other nearly every weekend. When Lowery was shot, his network of friends shared information, memories and support. On Nov. 12, Altman, 70 miles from Lowery’s bedside, received constant updates about his friend’s condition from those present in the hospital.

“As soon as he passed at the hospital after surgery, I knew, and it absolutely devastated me,” Altman said. “I lost my brother.”

A funeral and memorial service were held for Lowery on Saturday, Nov. 17. Members of the class of 2010 planned a gathering in Athens that same night to remember their friend and classmate.

“We all wanted to get together and just be with each other for moral support,” Altman said. “No one needs to be alone at times like these. Being around your friends is what helps.”

To many, Lowery’s murder was all the more tragic because the class of 2010 had already lost two members: Jay Jackson in June 2012 and Kaveh Sadri in October 2011. Campis agreed the impact of the deaths was broad.

“The class of 2010 lost three people in the last year,” Campis said. “It’s hard for everybody even if you didn’t know him. It’s almost scary knowing someone you went to high school with and not that much older than you [was killed]. It can affect you.”

Bonner attended the funeral in Atlanta and said she was comforted by the strength she saw displayed by Lowery’s mother Allison Webb and girlfriend Emma Jackson, who graduated from Grady in 2012. But each mind was focused on the senseless loss of a young man who spent a short lifetime smiling and making others smile.

“I think the pastor said it: if anybody needs to be here today it would be Lee because he would brighten the whole mood,” Bonner said.

Webb said she hoped to establish a scholarship fund, to be called The Lee Project, to keep Lowery’s memory alive. The funds will be awarded to students who are not only academically successful, but also give back to their communities.

“Maybe this time next year we can start helping some kids and doing it in his honor,” Webb said. “And having more people like Lee impact a lot of people. That keeps me kind of going.”