Social studies teacher James Campbell frequently jokes to his students that he “has people everywhere.” Recently, Campbell undertook a task that made him wish he wasn’t joking.

Beginning at the end of the last school year and continuing over the summer until the end of September, Campbell and registrar Chinaester Holland attempted to locate students who left Grady before they graduated, starting with students who would have graduated in 2011. Some of those students departed two or three years ago, Holland said.

Holland and Campbell were required to undertake this search for students because of a change in the way Georgia schools calculate graduation rates.

Prior to the 2010-2011 school year, Georgia and several other states used the leaver formula to calculate school graduation rates, Georgia Department of Education spokesman Matt Cardoza said. Beginning with the class of 2011, the U.S. Department of Education required all states to calculate graduation rates using the cohort formula.

The leaver formula allowed schools to count students who took up to six years to complete their coursework as graduates, and to assume that students who withdrew graduated from a different school. Under the cohort formula, if a school cannot prove that a student who withdrew later enrolled in another school, that student is counted as a dropout.

Sean Mulvenon, a professor of educational statistics at the University of Arkansas and director of the National Office for Research on Measurement and Evaluation Systems, said the cohort formula is considered more accurate, but many states previously used the leaver rate.

“This is a systemic problem that they’re having across the country,” Mulvenon said. “The graduation rates were just inflated.”

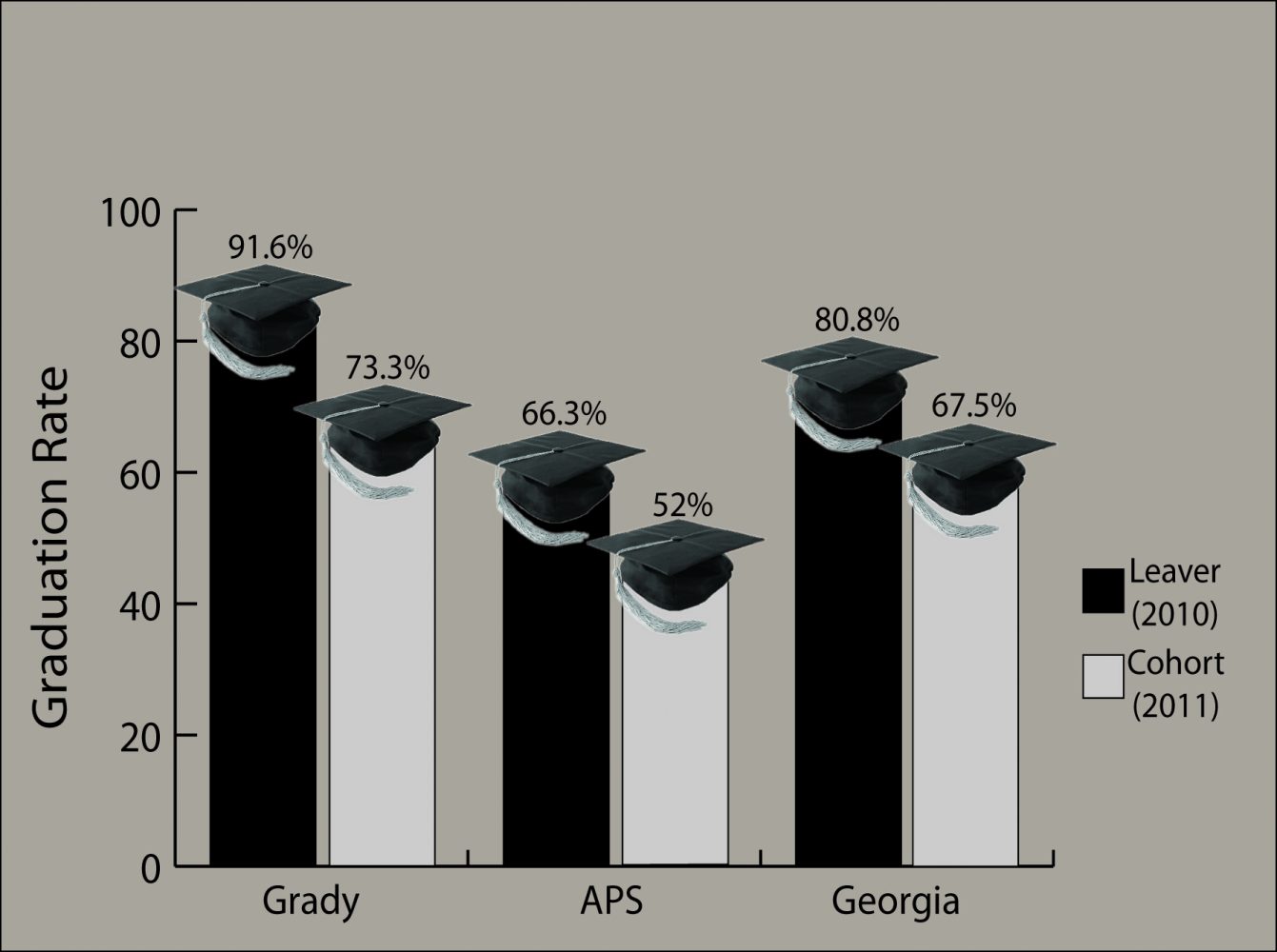

The formula change caused graduation rates statewide to plunge. According to the Georgia DOE website, Grady’s graduation rate for the class of 2010 was 91.6 percent; for the class of 2011, it was 73.3 percent.

Holland said prior to last year, when graduation rates were still calculated using the leaver formula, the only documentation needed for a student to withdraw was a parental consent form. The form asked parents to list their intended location and the name of the school their child would attend. Under the new system, that form is not proof a student enrolled elsewhere; if Holland cannot obtain a transcript or tuition receipt from the new school, the student is counted as a dropout.

Holland has now changed the withdrawal procedure so that students who transfer from Grady must send her proof of their enrollment at a new school. Students from the class (or cohort) of 2013 who transferred before last year, however, will be counted as dropouts if Holland cannot establish proof of re-enrollment.

Campbell said if a student enrolls in another Georgia public school, the Statewide Longitudinal Data System tracks the student’s whereabouts, allowing administrators to confirm the student did not drop out. If a student enrolled in a private school or a school in another state, however, Holland and Campbell must use what Campbell terms “people-finding tools.”

Holland said she begins by looking at the withdrawal form the student provided when he or she left Grady. If the parent indicated the name of the school at which the student intended to enroll, Holland calls the school and requests a transcript. Often, however, students moving out of state do not know which school they will be attending. Then, Holland turns to the information on a student’s Infinite Campus profile. In some cases it has been years since the student attended Grady, so the phone numbers may no longer be in use.

If the contact information is incorrect, she turns to the Internet. Holland said she searches students and their relatives on Facebook, hoping to track down someone who can lead her to the student.

Sometimes, Holland and Campbell find information about students by asking teachers and current students for leads.

“I turn into a detective,” Holland said. “Some kids you know … they’re like in orchestra or ROTC. You kind of know what they did when they were here.”

Holland has found students in Russia and Spain. She worked through the list until the deadline, Friday, Sept. 28, but estimated she was unable to find half the students.

Some of the missing students may have already graduated or be on track to graduate—but if they can’t be located, they will be counted as dropouts, reducing Grady’s reported graduation rate for the classes of 2012 and 2013, Holland said.

Grady’s graduation rate is particularly important since Georgia began implementing its Race to the Top reform plan last year. Based on graduation rate, test scores and other performance measures, schools may be designated Priority, Focus, Alert or Reward Schools by the Georgia DOE.

Reward schools are the highest-performing Title I schools, while Priority Schools are the lowest-performing. Focus Schools have gaps in achievement between subgroups, and Alert Schools may perform poorly on some metrics but are deemed stronger overall than Focus and Priority Schools.

Because of the wide disparity in graduation rates between the highest-achieving subgroup—white students—and the lowest-achieving subgroup—students with disabilities—Grady was named a Focus School in March 2012.

Grady is the only APS high school on the Focus list, although many APS high schools are Priority Schools.

Campbell said it is unfair to single out Grady when other schools may have a smaller achievement gap but lower performance across the board. He also believes the system is flawed because many subgroups overlap.

Mulvenon, the University of Arkansas professor, said the overlap of subgroups does not mean the data are incorrect or illegitimate.

“[Teachers] have complained about that since the beginning of No Child Left Behind,” Mulvenon said. “That’s all you ever hear, ‘it’s not fair, it’s not fair, it’s not fair.’ I think it’s not fair that these kids don’t graduate.”