Emory University erupted in a controversy Sept. 14 when Robin Forman, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, sent a letter to students explaining the university was closing its Division of Educational Studies, department of physical education, department of visual arts and its journalism program. Forman also wrote that Emory would suspend admissions to graduate programs in Spanish, economics and the Institute of Liberal Arts, and would reduce funding for other areas of the university.

Forman wrote in the letter that the cuts are intended to “increase our investment in our current areas of scholarly and educational distinction as well as to develop new strengths in both existing disciplines and emerging areas of inquiry.”

In a similar letter to graduate students, Lisa Tedesco, dean of Emory’s graduate school, confirmed the changes to the graduate school that Forman had explained, and invited discussion of the new directions announced by Forman.

“There are some departments that are being phased out, but the hope is to generate funds to grow other departments,” Forman said in an interview with The Emory Wheel. “This is about making the College better. It’s not a department-by-department decision.”

Forman, Tedesco and Emory president James Wagner all declined to speak to The Southerner.

In his letter, Forman stressed the cutbacks were not due to Emory’s budget deficit, and emphasized that tenured faculty in the discontinued departments will be moved to other departments. Not everyone at Emory, however, is convinced the changes are positive.

Many objected to the lack of transparency during the decision-making process. Aiden Downey, an assistant professor in the Division of Educational Studies, said Emory’s decision came as a shock to the people in his division.

“I’m big on people being at the table when decisions are being made about them,” Downey said. “We’re not children. And it would be nice to know what’s going on.”

Samiran Banerjee, a senior lecturer in Emory’s economics department, agreed with Downey.

“To some extent, I feel that there was no due process,” Banerjee said. “When you do something that’s going to affect the lives of many people, then it behooves you to talk to them and tell them what are the consequences.”

Emory students also feel they didn’t have enough say in the decision. Ben Leiner, who double majors in economics and history, thought Emory should have included students in the decision-making process.

“There was no student representation in the decision-making process, and, frankly, the faculty in the affected departments were not adequately consulted when the decision was made,” Leiner said.

Calvin Li, however, a sophomore at Emory and the student-life chair for Emory’s Student Government Association (SGA), said he is not sure students would have had a positive influence on the discussion, though he did say administrators should have at least talked to some students.

“We would have preferred it had they consulted several student leaders to gauge what possibly could happen, to see if it would have been productive for students to have been part of the discussion,” Li said.

A letter from the SGA to the Emory community expressed concern that the administration’s decision-making process excluded the “involvement – or even awareness – of any current students.”

Many at Emory disapprove of the decision to eliminate graduate and undergraduate programs. Downey disagreed with the Dean’s decision to eliminate the Division of Educational Studies.

“People say how can an educational institution cut its education program? That’s a good question we’re still trying to get answered,” Downey said.

In an SGA meeting on Sept. 17, Forman said the College does not have the resources to support the many economics undergrads. But Banerjee is worried the cut will cause the economics department to lose faculty.

“It’s one big giant equal system, in which the Ph.D. program is kind of central, so that’s like the source of water, so if you cut out that water, then everything dries up,” Banerjee said. “Once you get rid of the Ph.D. students, you can’t do any research in the department.”

Leiner said that this will cause faculty to leave Emory.

“For those who are on the edge of retirement, or for those who are regularly sought after by other institutions, the lack of a graduate program is going to push these faculty members either away from Emory or into retirement,” Leiner said.

In an editorial for The Emory Wheel, Leiner said that the cuts are pushing undergraduates toward the Goizueta Business School by dismantling the economics department.

Forman stressed in his letter that students currently enrolled in the departments being cut will be able to complete their courses of study. But Banerjee is worried this loss of faculty will negatively impact economics students’ education. Banerjee said it will be hard for the current Ph.D. students to finish their degrees with a lot of the faculty leaving.

“In all fairness, we can’t tell [the Ph.D. students] stay on, stay on, we’re going to take care of you, because we don’t know who’s going to be here to take care of them,” Banerjee said.

Banerjee said the elimination of the graduate program was especially surprising considering the department had finally cracked the top 50 of economics program rankings, according to a study by the University of North Texas a few weeks earlier.

Hank Klibanoff, director of the Emory journalism program and former managing editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, objected to the dean’s decision to cut the journalism program. He said the dean cut the journalism program because he thought a liberal arts education should be more broad-based, and journalism is a pre-professional track. But Klibanoff disagrees that Emory’s journalism program is strictly pre-professional.

“We are inherently and intrinsically an interdisciplinary program,” Klibanoff said. “And we are educating many people who have no intention of being a journalist.”

He said Emory’s program is unique because students can’t major in journalism; they have to co-major in some other subject as well.

Jon Reese, adviser of Decatur High School’s news magazine, Carpe Diem and an Emory graduate, agrees that the Dean’s argument wasn’t a particularly strong one.

“If they were already co-majoring, that demonstrated their interest and their requirement that they be pursuing a wider-scope program,” Reese said.

Some students are worried about the long-term impact of cutting liberal arts programs.

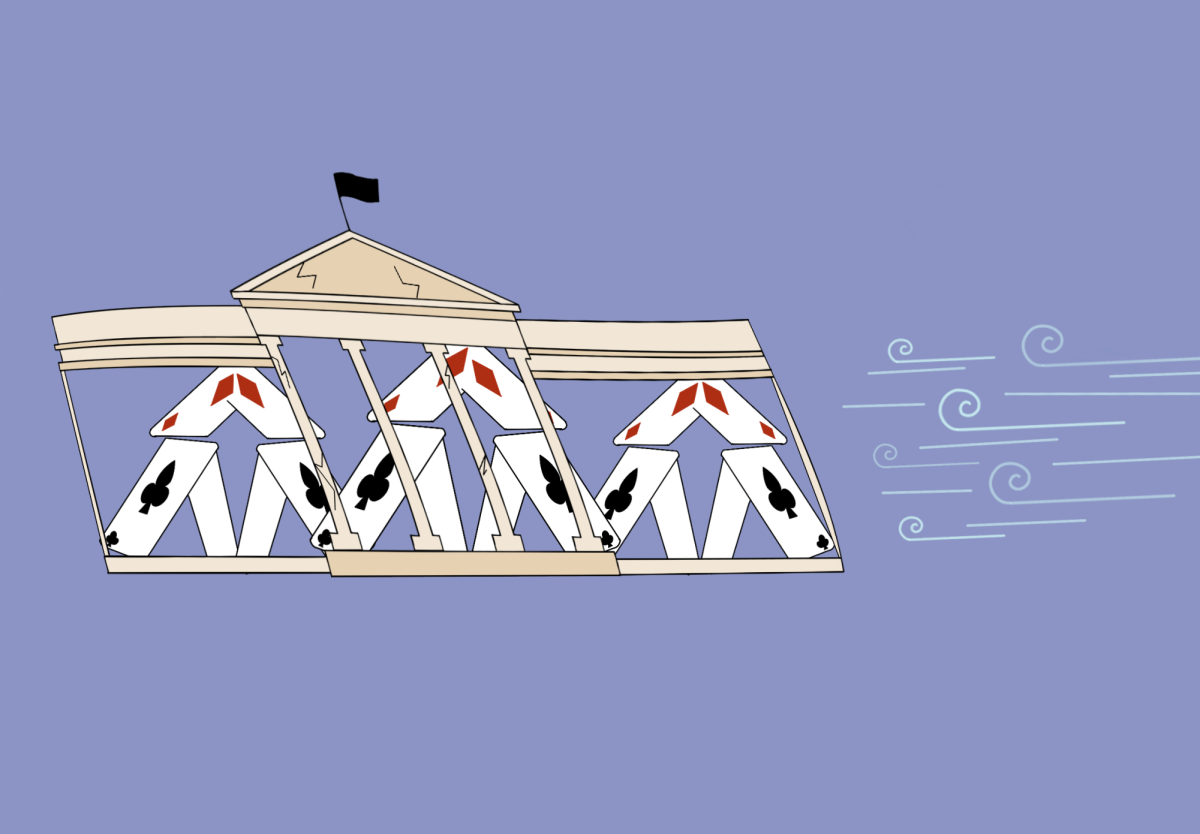

“I think that the fact that these cuts have been handed down reflects Emory’s movement away from this liberal arts model towards a more pre-professional model where medicine and business are the primary goals of the institution, and I think that it sacrifices the well-roundedness of an Emory education,” Leiner said.

Jonathan Demar, a senior journalism student at Emory, is worried the cuts reflect a national trend away from liberal arts.

“Liberal arts is what’s going to keep this school alive, and so when you get rid of liberal arts, you’re getting rid of what fundamentally the Emory we love and care for is,” Demar said.

Many members of the Emory community are taking to social media to oppose the changes. English graduate student Claire Laville started a blog called “Stop the Cuts at Emory,” Banerjee created a Facebook group called “Save the Economics Ph.D. Program at Emory,” and Demar helped start the Facebook page called “#EmoryCuts” to spread the word about Emory’s downsizing. An online petition entitled “Emory University: Rescind the Cuts or No Alumni Donations” has also garnered 41 signatures.

Meanwhile, Forman and the rest of the Emory community, with the support of President Wagner, are moving forward with the cuts. Whether they will create a brighter future for the university, however, is yet to be known.