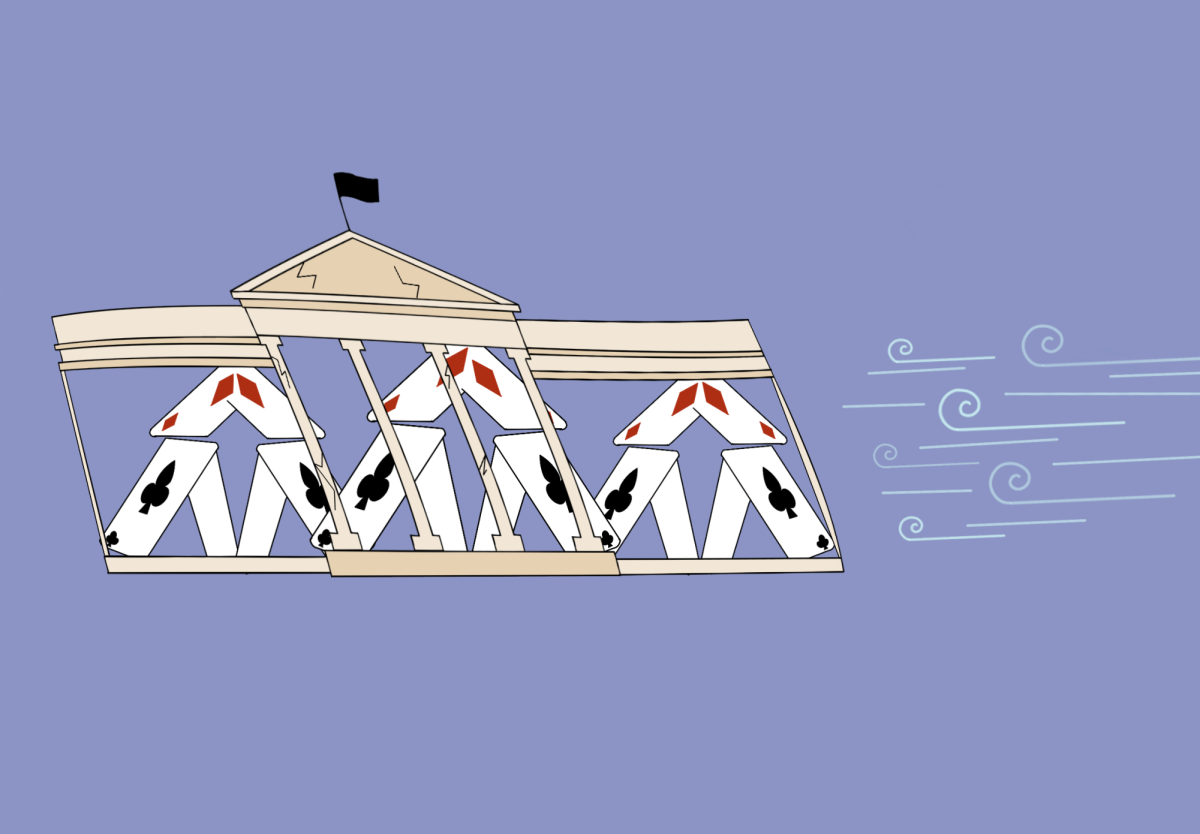

With the tumult surrounding legislation on the Common Core State Standards and gun rights, the 2014 legislative session got plenty of attention from stakeholders and the media. Several important bills related to charter schools, however, largely escaped the spotlight. In the debate over these bills, a fundamental dispute at the heart of the school choice movement was revealed: whether a free market-based system that encourages competition and choice can be applied in education or whether it leaves certain students behind and goes further down the road to the privatization of the public education system.

With the tumult surrounding legislation on the Common Core State Standards and gun rights, the 2014 legislative session got plenty of attention from stakeholders and the media. Several important bills related to charter schools, however, largely escaped the spotlight. In the debate over these bills, a fundamental dispute at the heart of the school choice movement was revealed: whether a free market-based system that encourages competition and choice can be applied in education or whether it leaves certain students behind and goes further down the road to the privatization of the public education system.

House Bill 123, or the Parent and Teacher Empowerment Act, was one of the bills that was considered, though it did not pass. It is known as a “parent trigger” bill, meaning it would allow parents, by a majority vote, to “pull the trigger” on a school and either turn it into a charter school or remove the school leadership. Janet Kishbaugh, a lobbyist for the Southern Education Foundation and a Grady parent, said the bill would make it too easy for parents to force radical changes.

“It literally says a majority of parents would have to vote for pulling the trigger and it would be parents who show up at a meeting,” Kishbaugh said. “So if you had a meeting and like 50 people came and 26 people voted for it, you would successfully pull the trigger.”

Carolyn Wood, also a Southern Education Foundation lobbyist and Grady parent, agrees, saying the bill would be “incredibly destabilizing to traditional public schools.”

HB 897, which also relates to charter schools and didn’t pass, is what is known as a “Title 20 rewrite” bill, meaning it makes many small fixes to the state’s education code. Wood thinks this bill goes too far in its charter school provisions.

“It’s not unusual to have a cleanup bill for Title 20,” Wood said. “What’s unusual in [HB] 897 is to have so many substantive charter school provisions in the bill also that takes it out of the realm of a pure cleanup bill and it adds any number of substantive provisions for charter schools, some of which are really to the detriment of the traditional public school system.”

Kishbaugh said pro-charter lobbyists, who far outnumber pro-traditional public school lobbyists and are much better financed, saw the law as a way to accomplish some of their legislative priorities. One charter-related provision of the bill is the establishment of a nonprofit foundation to receive grants from private donors for state charter schools. Kishbaugh argued that this simply provides charter schools a superfluous source of funding.

“There’s a whole separate source of funding for charter schools, which is great for them, but isn’t available to traditional public schools,” Kishbaugh said.

Andrew Lewis, executive vice president of the Georgia Charter Schools Association, insisted that the newly established foundation is simply the equivalent for state-approved charter schools of the nonprofit fundraising arms of local school districts.

“I’m not quite sure in my mind what the uproar has been about the Commission being able to establish a 501(c)(3) to receive grants,” Lewis said. “I think some of the misinterpretation is that this is an attempt to raise money to pay for students to attend these charters and that is certainly not the case.”

Matt Jones, the executive director of EmpowerED Georgia, an education advocacy organization, sees a conflict of interest in the foundation.

“There could be a lot of glaring conflicts of interest there, where you could have some for-profit charter management company donating to this foundation being administered by people who are approving charter petitions, a lot of which could be for-profit management companies,” Jones said.

State Rep. Mike Dudgeon, the bill’s author, disagrees, arguing that the provision simply provides a mechanism for the State Charter Schools Commission to do what it was granted the power to do in the 2012 amendment that established it.

“All we’re doing in this bill is adding the thing that was accidentally left out in 2012,” Dudgeon said.

Another controversial provision of the law requires that, if a traditional public school is using less than 40 percent of a facility, then the rest of the facility must be made available for use by local charter schools. Lewis said this provision is necessary because of districts like DeKalb County.

“Even though there are over a dozen unused district facilities [in Dekalb County], only in the past two years have they made three of those facilities available to their own locally approved charters,” Lewis said.

Kishbaugh argued that the 40 percent statistic is arbitrary, which Lewis admitted.

“They just pulled it out of the air because it was less than 50 percent,” Kishbaugh said.

Lewis emphasized that, though it is possible that charter schools could share a facility with a traditional public school under the new law, this type of arrangement has been implemented successfully in New York City. Kishbaugh, however, sees potential friction.

“You can have situations where you have one part of the school being operated by a charter system with a charter principal and all of their rules and all of their flexibility that’s given to a charter, and the rest of the school is still running under the traditional school model with a different principal and a different administration, and completely different rules,” Kishbaugh said.

Kishbaugh argued that these provisions, combined with several others in the bill, make the overall law a very charter-friendly one.

“A lot of that is just really fine points and things,” Kishbaugh said, “but the overall tenor of everything is to try and expedite the ability of charters to be created and get approved.”

Another bill that was considered last session was HB 759, which would expand Georgia’s tax credit system providing students scholarships to attend private school. Though the bill didn’t pass, the program remains controversial, as some don’t think there is enough accountability and oversight to ensure the the program is truly helping low-income students in failing schools.

“Georgia is one of the few states that doesn’t require any assesments for students that take advantage of the tax credit scholarship or voucher program, so we don’t really even know how students are doing,” Jones said, adding that “scholarship recipients are not required to be low-income, and there’s no requirement that they be first attending chronically underperforming school.”

Wood said some of the student scholarship organizations that participate in the program do require that the students who receive the scholarships qualify for free and reduced lunch, but others don’t.

“Right now, this appears to be a middle and upper-class boondoggle,” Wood said.

Jay Bookman, an opinion writer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, sees an even more insidious motivation behind the program.

“People want to have their kids in schools with other people like themselves,” Bookman said. “It’s a way to opt out of the public system, in which everybody’s forced together and forced to figure things out together. It’s a way to opt out of that system, using public money to finance it.”

Claire Suggs, a senior education policy analyst at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, argued that the state can’t afford to funnel $58 million in tax revenue every year into private schools, when its traditional public schools are reeling from austerity cuts.

“These programs defer tax revenue to the state, so revenue that would otherwise be coming to the state is actually going directly into private schools,” Suggs said, “and at a time when we have cut funding for public education—for the current school year, we have an austerity cut of $1 billion—we can’t afford to lose any dollars from the state revenue.”

With all of this money flowing from public schools into private schools, Wood sees the school choice movement as a step toward the privatization of public education. This movement, Wood argues, doesn’t account for the most disadvantaged students in Georgia.

“Who gets left behind [from the school choice movement] are our most vulnerable students, our most difficult to educate, our students who are English language learners, our students with special needs … our poorest students,” Wood said, “and I think it’s our obligation, as a society, to educate our entire population.”

Bradford Swann, state director of the national education advocacy organization group StudentsFirst, disagrees, arguing that choice is a positive thing for students, especially those from low-income families.

“[The school choice movement] is more about giving choice to everyone, including those who really have no choices currently, than it is about anything else,” Swann said.

Jones argues, however, that the choice is not made by the students, since the schools are the ones choosing which students to admit.

“Is it really true competition if you have one school that does not provide transportation, or one school that can pick the students that attend the school, and have all these barriers and hurdles just to get into the school?” Jones asked. “Compare that with another school that has to accept every child that walks in their door.”

Jones sees hypocrisy in the privatization movement, and the education reform movement as a whole.

“For private schools … we see very small class sizes, we see a rich curriculum, we don’t see a lot of testing, we see experienced teachers,” Jones said. “And yet, when we’re looking at the traditional public schools, and quote ‘reform,’ then the same people that tout these private schools as good examples of good schools are pursuing the opposite with public schools.”