Once an activity reserved for wealthier suburban school systems, urban debate leagues popping up in inner-city schools are finding that this old-time activity can help at-risk students turn their lives around.

Sean Bennett, a teacher at the Fayette County Alternative School, implemented an idea that he believed would help troubled teens change their lives: at-risk students, who have gone through the juvenile court system, could benefit from being part of a competitive debate league.

“I always thought the idea was really just a brilliant concept,” Bennett said. “And I knew from being a debate coach for 13 years that debate had amazing effects on students, especially at-risk students.”

Bennett, along with the help of the nonprofit organization Hearts to Nourish Hope, created a debate league to aid at-risk youth in developing conflict-resolution skills. The league formed two Lincoln-Douglas teams from Fayette and Clayton counties. The teams, created in conjunction with the Department of Juvenile Justice, competed in their first Lincoln-Douglas debate at the Warner Robins Debate Tournament last May. Since then, the program has skyrocketed, quickly making a name for itself throughout the state.

“I’d like to be able to expand into other areas,” Bennett said. “It would be really good if we had a network of teams because we’ve proven it works. Now it’s just a matter of having other people model that same pattern.”

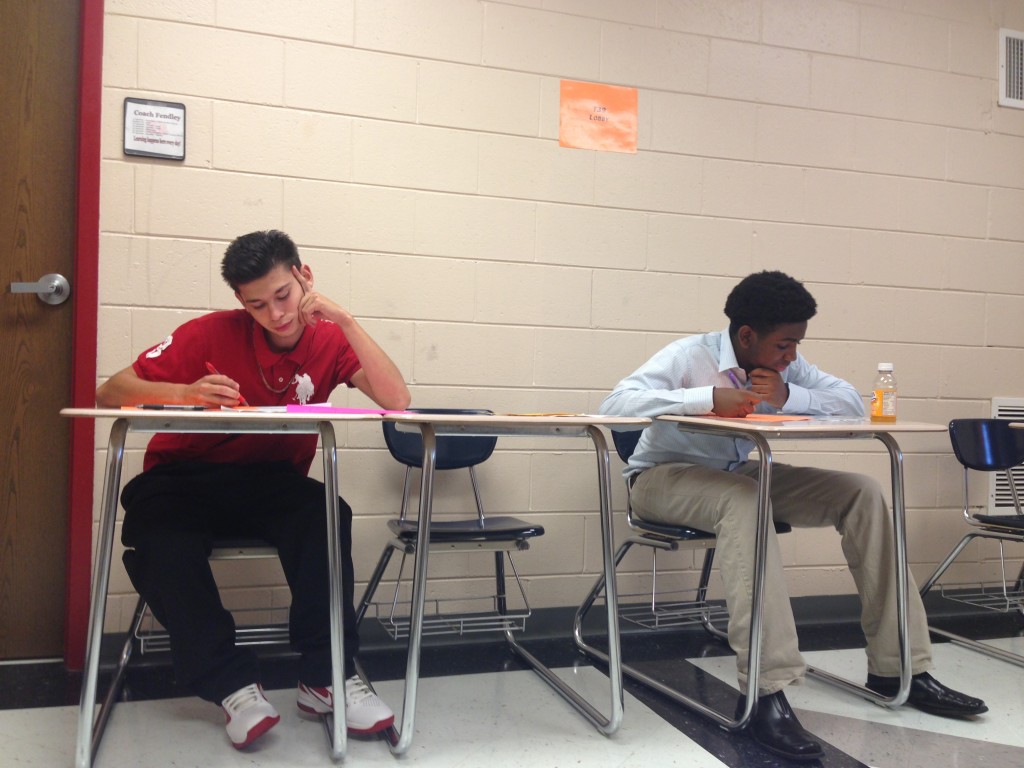

The team meets twice a week to prepare for tournaments. Right now they are preparing for the National Catholic Forensic League’s National Championship. They were invited to the tournament because of their outstanding performance at the Peach State Classic in November. They continue to learn about persuasive techniques, speaking skills and argumentative strategies.

The students who comprise the juvenile justice debate league are all on probation. Some have been to prison, some just to court, but all have been involved in the juvenile justice system of Georgia in some way. Bennett said that from the beginning the program had two goals: to learn the communication skills needed to address their problems and to improve critical-thinking skills.

“What we really wanted to do was expose these kids to debate and the environment, and we wanted to help them figure out how to interact with people in their lives better,” assistant coach Megan Harrison said. “It’s about learning how to present yourself, learning how to use rhetoric in the art of being able to speak in a convincing and established way.”

Grady’s own speech and debate coach, Lisa Willoughby, agrees. She believes that one of the greatest successes for coaches is seeing their students engage in the program and use it to help them get through difficult times.

“The hope is that participating in the justice league will help kids learn that they can use language and words, rather than physical violence to resolve conflicts,” Willoughby said. “The initiative is an exciting opportunity for the students, and for the most part, I think the experience that they’ve had is really positive.”

Coincidentally, the February Lincoln-Douglas topic was “Resolved: Rehabilitation ought to be valued above retribution in the United States criminal justice system.” Bennett recalls uncontrollably laughing when he heard the topic for the first time in a meeting.

“I said on my left-hand side I have rehabilitation, and on my right-hand side I have retribution,” Bennett remembered. “So the department of juvenile justice was on one side and then a nonprofit organization that tries to help kids and rehabilitate them was on my other side.”

The final debate round was held in the juvenile court, and the judges were juvenile-court justices. Because the topic was so applicable to many of the students, studying the topic became very personal for many of them.

“These kids debated the final round in the courtroom where they were originally convicted in front of the judges that originally convicted them,” Bennett said. “And the topic was rehabilitation versus retribution. I don’t know if I’ve ever had a more ironic moment in my entire life.”

Bennett and Harrison say that experiences like these reveal the magnitude of the impact that this debate program has made for many of its students. In fact, a significant number of these students have not only graduated from high school, they have even gone on to return to their original high school and join debate teams.

According to research by the Urban Debate League, urban debate prepares students to succeed in school and in life. It creates a significant increase in the graduation rate and the number of students who go to college. In fact, 90 percent of urban debaters graduate on time, and after graduating from high school, 86 percent of urban debaters enroll in college. Harrison believes, however, the most important thing is that urban debate empowers students and teaches them that they have a voice.

“That’s why debate is such an empowering tool,” Harrison said. “It gives you the ability to tell your story, in your terms. A lot of these kids don’t really realize how powerful their voice and their opinion is. I want them to know that their viewpoint matters, and that if they can go about it in certain ways, people will listen to them.”