Each Friday afternoon when Vanessa Morton enters room E210, nine students rise to their feet to commence their training for the Special Olympics. She pops in an exercise video displayed on the Promethean board to begin her lesson with the nine students in Grady’s self-contained autism class.

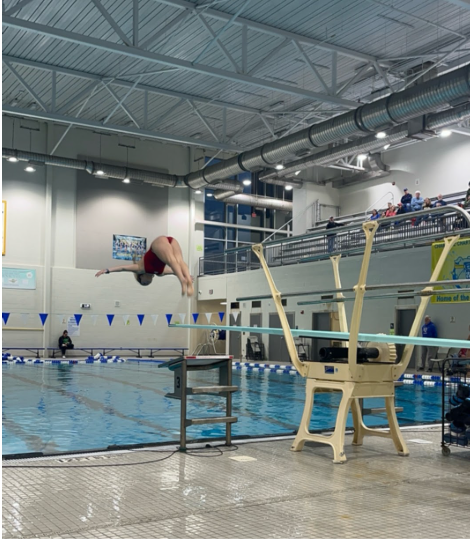

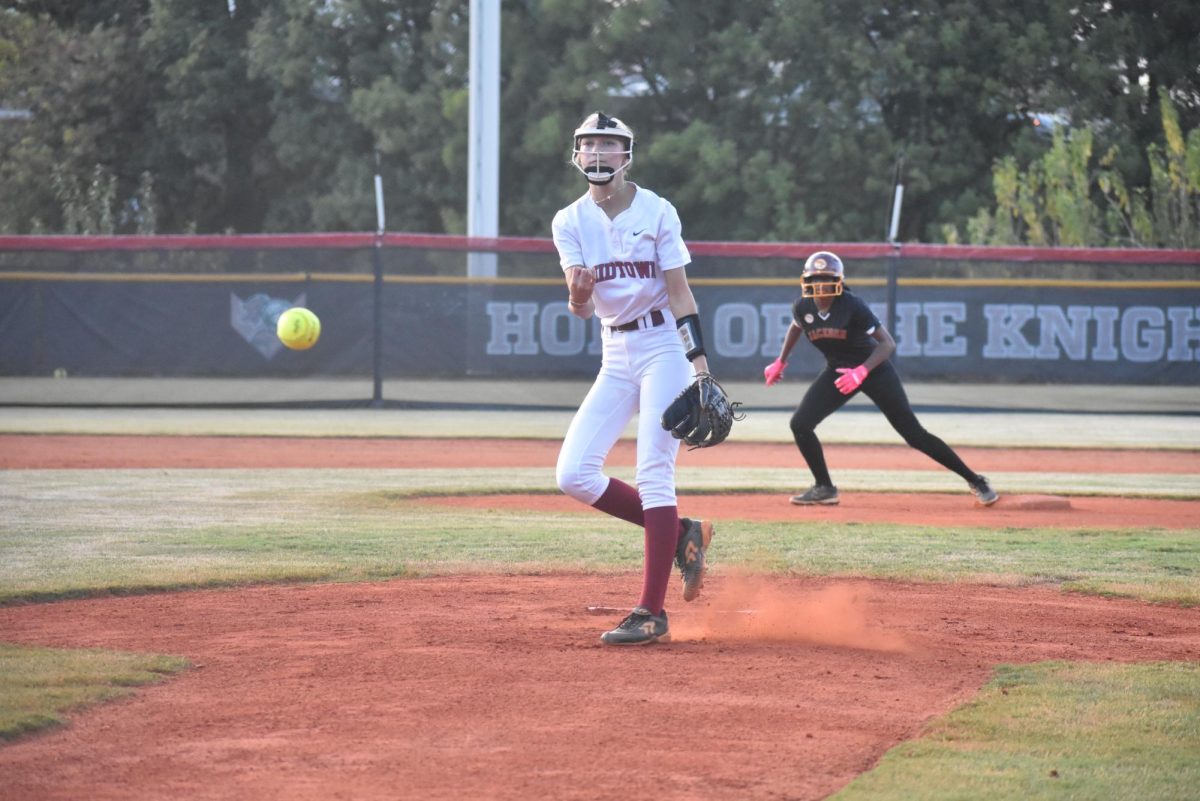

As an adapted physical education teacher, Morton modifies traditional physical education curriculum to address the individualized needs of students with disabilities. So far, those athletes have shown success in bocce, softball and basketball competitions and are currently preparing for the next event: bowling.

The mission of the Special Olympics is to give children and adults with intellectual disabilities opportunities to develop physical fitness, demonstrate courage, experience joy and participate in the sharing of skills and friendship with their families, other Special Olympics athletes and the community. This is accomplished by providing sports training and athletic competitions in a variety of sports competitions that are spread out throughout the year, and Grady students are taking advantage of this opportunity.

In 1970, 500 students gathered at a suburban Atlanta college to participate in the first event held under the Georgia Special Olympics banner. Since 1970, the number of active athletes in the competition has grown to more than 23,000 students who participate in a total of 24 sports.

“[The athletes] see sports games on TV, and they see what their peers can do, and now they can do it too,” said Regina Gennaro, the APS liaison for the Special Olympics.

She said there are several levels of difficulty in the competition, each with different tasks to fit students’ diverse capabilities, so they are all able to participate.

“If all they can do is pick up a ball, then great-they’re still a winner,” Gennaro said.

Before rounds of competition during the Georgia Special Olympics, an oath unites the voices of all competing athletes: “Let me win, but if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt.” Gennaro, however, said all of the students feel like winners solely for participating.

The competition also promotes development of skills outside of sports.

The athletes gain skills for employment, learn independent living skills and help others understand their capabilities despite health issues.

In addition to Morton and Gennaro, four other coaches from around APS have invested their time to guide the athletes: Wendell Hale, Lisa Oglesby, Nic Hill and Patricia Merkerson.

Morton said she has watched some of the students’ progress since teaching them in elementary or middle school.

“I used to be pulling teeth just trying to get them to participate in anything,” she said. “Now several of them keep asking when the next event is and really look forward to it.”

Freshman Deandre Ford was one of the 12 students selected from APS to participate in the state softball competition.

“It was fun,” Ford said. “I got to meet a lot of new people.”

His mother Tonya Ford believes the competition has helped enhance her son’s outgoing personality.

Latonya Whatley, another parent, remembers when her autistic son, Darrius, proudly displayed a ribbon he earned in the competition. She said he often expresses his excitement after completing activities and now likes to spend more time with his siblings.

“[The Special Olympics] helps him be more sociable,”Whately said. “It’s hard because of his disability.”

Russie Ruelemore, whose son Brandon also has autism, said she is glad to see the students excited about playing sports.

“A lot of the time, people shy away [from people with disabilities],” Ruelemore said. “People say they are different, but who is to say they aren’t different themselves?”

Hale, who is on Grady’s special support staff, has also spent time coaching regular athletics. He said he has come to realize that coaching for a special needs team can be very different.

“[The Special Olympics] gives them some more confidence and a real sense of belonging,” Hale said.

He said he is glad to donate his time to coaching students and encouraging them to achieve success.

“I’m volunteering, but it feels like I’m being paid,” Hale said. “There is no price for it.”

Gennaro is one of the more than 15,000 volunteers in Georgia who are dedicated to promoting the growth and development of athletes. She has been very involved in the Special Olympics for almost 30 years.

By reaching out to volunteers, Gennaro believes she is spreading the word about what students can do despite their disabilities.

“I love getting other adults involved and standing with me to share this amazing experience,” Gennaro said. “It has a domino effect.”