In early October, Mandie Mitchell, an artist and gallery owner, was evicted from her live-work space when she was unable to continue paying her rent. Mitchell and her daughter Mackenzie, a fifth-grader at Cook Elementary School, found themselves homeless. Instead of turning to relatives or a homeless shelter, the Mitchells set up a tent in Woodruff Park in downtown Atlanta, joining roughly 200 others in the protest movement called Occupy Atlanta.

Inspired by Occupy Wall Street, the protest against banks and corporations in downtown New York City, Occupy Atlanta began on Oct. 7. Hundreds of people alerted by word of mouth and a Facebook event page converged on Woodruff Park—which was renamed Troy Davis Park by the demonstrators—to express a litany of grievances aired by Occupy movements across the globe.

The protesters, along with their signs and tents, remained in the park until Oct. 25, when Mayor Kasim Reed ordered the police to evict the protesters. The police arrested more than 50 people.

Senior Holden Choi and Grady graduate James Holland, now a sophomore at Georgia State University, were among the crowd in Woodruff Park on the first night of the protest.

The demonstrators implemented protocol for speaking at their General Assembly, the nightly meeting at the park to discuss and debate the status of the protest. They then established rules for living in the park and approved a list of 11 grievances that drive the movement.

“Our system was consensus,” Holland said. “If we weren’t in complete agreement about a plan, we wouldn’t do it. It took about two hours to reach the agreement to occupy the park.”

Many occupants at Woodruff Park said they view the movement as a way to raise awareness about economic injustice and foster discussion about possible solutions.

Protesters celebrated the community that developed in the park. Kimlee Davis, a freshman at Georgia State, said she and others forged friendships over discussions of political issues, preparations for potential conflict with the police and the simple acts of daily life that became more difficult while living in a tent in downtown Atlanta.

“We’re all like a family out here,” Davis said. “We call each other brothers and sisters.”

During the day, protesters offered workshops on topics such as interacting with the police and growing vegetable gardens in pots. A medical tent offered basic first aid, while a child-care tent provided games and toys for children.

“We want to make it so people feel comfortable coming here with families,” said Maris Gill, a Georgia State junior who headed the child-care committee. “There are maybe 10 to 12 kids here right now.”

An art tent provided supplies to make protest signs to carry on demonstration marches, which happened nearly every day against targets including the Georgia-Pacific building and the Federal Reserve Bank. James Malone, director of communications for Georgia-Pacific, encountered the protesters as he left work one evening but found them peaceful and calm.

“Everybody has the right to a democratic voice,” Malone said. “Georgia-Pacific respects the right of everyone to protest.”

Occupy Atlanta received numerous donations of food, tents and clothes, which were distributed to the protesters free of charge. “The Free Store,” set up on a folding table in the middle of the park, offered odds and ends such as a pair of Crocs, a worn copy of Goodnight Moon and a plastic dustpan.

“Everyone’s sharing their food, skills and supplies,” said Mandie Mitchell, who led a workshop on jewelry-making while she was living in the park.

Woodruff Park has long been frequented by members of Atlanta’s homeless community. Attracted by free food and shelter, many joined the movement.

“When you don’t got nowhere to sleep, and they got a tent, you’re gonna take it,” said James Crider, who has been homeless for three years. “What the media doesn’t say is that the majority of people out there are homeless.”

Many protesters, such as Occupy Atlanta spokesman Tim Franzen, stressed the importance of including homeless people in the movement. Choi, however, believes the presence of “crazy homeless people” increased negative perceptions of Occupy Atlanta. He noticed a definite increase in the number of homeless people from Oct. 7 to Oct. 23, the last day he went to Woodruff Park.

“Instead of being political, the movement just became ‘let’s shelter all of society’s rejects,’” Choi said. “There’s a time and a place for that, but not when you’re trying to start a political movement.”

The colorful tents, arranged haphazardly over a large swath of grass, drew the attention of nearly all passers-by and the irritation of some.

“Some people will be like ‘Keep up the fight! I wish I could be out there!’” Davis said. “But some people throw eggs and come out with megaphones at 6 a.m. when everyone’s asleep.”

Junior Bilal Vaughn, who lives in an apartment across the street from Woodruff Park, found the protesters obnoxious and questioned whether the movement can achieve its goals.

“I don’t know much about the movement, but I think camping out in Woodruff Park is a little ridiculous,” Vaughn said. “They bang pots and pans, and they have megaphones and yell random phrases.”

Dgindi Streeter, a Georgia State sophomore who works at the Jimmy John’s restaurant across the street from Woodruff Park, said she had few problems with the protesters and even delivered a catering order to the park on the second night of the occupation.

“They’re pretty peaceful,” Streeter said. “They tried to use our bathrooms, but we tell them they have to buy something like a cookie or a water at least.”

When the protests began, Mayor Reed issued an executive order to allow the protesters to remain in the park overnight.

“The park closes every night between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., and without that special executive order he [Reed] would have been allowing law-breaking,” said Sonji Jacobs-Dade, Reed’s director of communications.

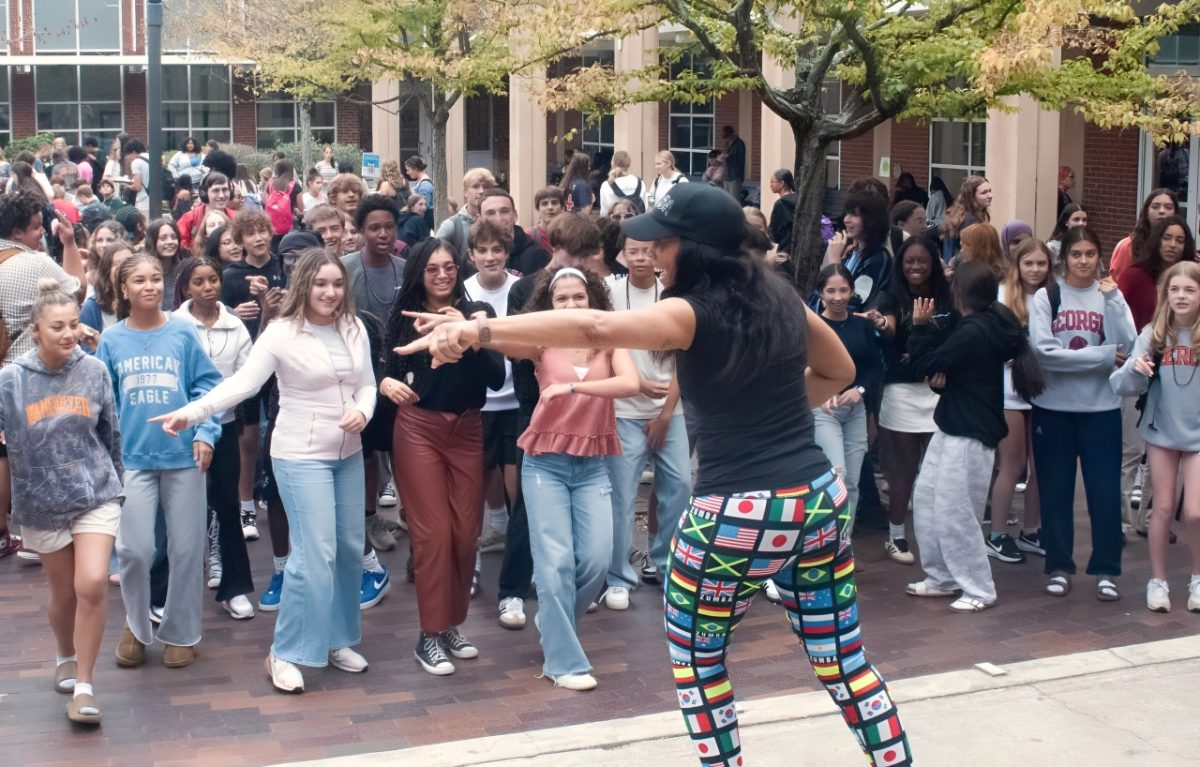

When the order expired on Oct. 17, Reed issued a new executive order to allow the protesters to remain in Woodruff Park until Nov. 7. He revoked the permit, however, after the protesters cooperated with a concert organizer to host a hip-hop concert in the park on Oct. 22.

“I think there was a moment where we thought Atlanta could be the first city in the whole world that had a mayor that got behind the occupation,” Franzen said. “He kind of blew it.”

Jacobs-Dade said the concert organizer lacked a security plan. When representatives from Reed’s office, including Jacobs-Dade, went to the park to discuss the issue with members of Occupy Atlanta, protesters shouted and cursed at them.

In addition, there were concerns about the presence of a man who called himself Porch and carried an AK-47 in the park. He claimed to be in the park to protect the protesters. Franzen said Porch was not associated with Occupy Atlanta.

“If you are part of a peaceful movement, then why do you need an AK-47?” Jacobs-Dade said.

On the night of Oct. 25, police assembled around Woodruff Park. Many protesters, fearing arrest, left the park voluntarily over the course of the day. Mitchell and other parents in the park acknowledged that they were not willing to be arrested and would leave the park if ordered. Jamar Stalling, a junior at Georgia State, worried about how an arrest would affect his future.

“I’m not getting arrested,” Stalling said. “I’m going to law school. I’m a part of this, but I have to be conscious of my decisions.”

At midnight, the police entered the park and arrested protesters who refused to leave. Fifty-two spent the night in jail. The next morning, a judge set a March 9 arraignment date for the protesters, who were released from jail in the afternoon.

The occupants temporarily moved to the Martin Luther King Jr. Center and also spent time in a homeless shelter downtown. In early November, they briefly reoccuppied Woodruff Park. Twenty protesters were arrested when they remained in the park after 11 p.m.

Choi expressed dissatisfaction with the outcome of the movement and what he saw as the gradual loss of momentum.

“By the end it was like a summer camp with nothing for people to do,” Choi said.

Franzen, however, remained optimistic that Occupy Atlanta would continue to be a force for change in the city.

“We will continue the occupation in some shape or form,” he said. “No question.”