By Shaun Kleber

Between the first day of school and Thanksgiving break, there were 71 school days. In that period, students at Maynard Jackson, Washington and Douglass high schools and their feeder schools missed a combined 2,670 school days—and that is just the unexcused absences.

A 2009 city ordinance mandated a daytime curfew on school days for people between the ages of 6 and 16 from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., but rather than punishing children for violations, it established harsh punishments for parents whose children are caught outside of school without an excuse, including up to 60 days in jail and a $1,000 fine. Although the Atlanta City Council passed the ordinance in 2009, the city is only now beginning to enforce it.

“It’s targeted at parents,” said Atlanta City Council president Ceasar Mitchell, who drafted and introduced the ordinance. “It’s part of a larger program we have to encourage parents to be very active and engaged and, at the end of the day, responsible for their child’s truancy.”

Grady social worker Elesha Williams believes the ordinance will be enforced at Grady soon—possibly next year. Administrative assistant David Propst said more than 300 Grady students have had 10 or more absences this year.

For now, APS is piloting the program at Maynard Jackson, Washington and Douglass high schools and their feeder schools, said Denise Revels, APS coordinator of social services.

Mitchell explained that the city council identified students in each of those clusters with excessive unexcused absences and invited their parents to come to a meeting. Representatives from APS, the police department and social services attended the meetings to explain the ordinance and offer assistance to parents.

“What we found … is that in some cases, parents either didn’t know that their child wasn’t going to school, and in some cases parents kind of knew there was a problem, but they were having trouble managing their child,” Mitchell said. “So this provided us with the ability to identify what the issue was and find help for these parents.”

Mitchell found that, following these parent meetings, the number of unexcused absences decreased in these clusters, and he believes this trend can and will continue as long as they continue to communicate with parents.

Revels said 64 percent of the parents who attended the meetings have seen improvements in their children’s attendance.

“As we increase awareness of the city ordinance, we’re seeing improvement in attendance,” Revels said. “That’s our goal. We just want kids in school.”

The sudden push to enforce this ordinance is coming from both APS and the Atlanta Police Department. APS director of media relations Keith Bromery said the school district is placing more emphasis on truancy because of new leadership—a new superintendent and a new head of curriculum and instruction.

“Our thing under the new administration is that they want to pull out all stops to make sure kids are in school,” Bromery said. “It was a no-brainer that they wanted to start doing right away, to redouble the efforts to find out why … kids are habitually truant, to find out what’s going on and have it corrected.”

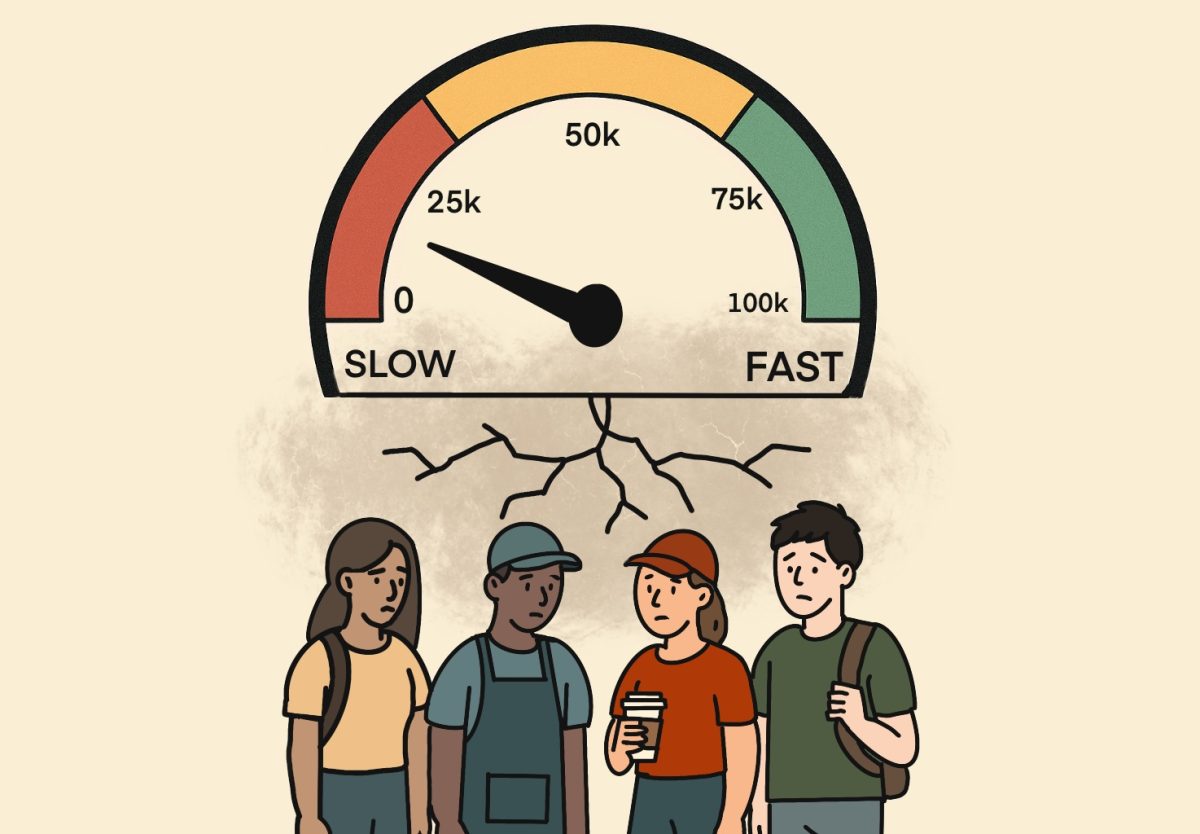

Revels said the police are increasing enforcement because they are concerned about the increase in juvenile crime, especially during daytime hours. She added that students with excessive absences are more likely to drop out of school, become the victims or perpetrators of crimes, become involved in the criminal justice system and diminish their earning potential.

“I think it’s important to bring those kinds of things out,” Revels said. “These are the reasons we are trying to make sure our kids stay in school, because we know that if they don’t, they’re headed down the wrong path.”

According to the ordinance, a parent is given a warning citation the first time his or her child is caught in violation of the daytime curfew and can be subject to a fine or jail time for subsequent violations. The child must also be out of school because of the “permission or insufficient control” of the parent in order for the parent to be penalized.

Some people disagree with the idea of punishing parents for their children’s truancy. Williams believes the punishments are appropriate when the parents are at fault and fail to change after other interventions. She concedes, however, that the policy is too severe as a blanket punishment.

Caren Cloud, staff attorney for the Georgia Truancy Intervention Project, believes parents should not be punished for the actions of their kids, who know they are supposed to be in school, and said the focus should be on fixing the problem rather than on punishing parents.

“There’s always a cause,” Cloud said. “There’s always something going on.”

Mitchell, however, said that if a parent knows his or her child is not going to school, the parent should be held responsible because “that parent is not doing a service to that child.”

Since the ordinance has not been enforced until recently, very few people have felt its effects. Williams said she has never cited a parent to face imprisonment or a fine, and Revels said there have only been four instances of that so far this year in APS.

Mitchell said imprisoning and fining parents is not the goal of the ordinance. He hopes the law will open the lines of communication with parents in order to find other solutions before resorting to these punitive measures.

“It is not our objective to put parents in jail because that just compounds the problem,” Mitchell said. “However, if we have parents we find in the court repeatedly for this … then I hope that the judges will use everything in their power … to inspire these parents to step up to the plate and manage their child better.”