Stretching from the Piedmont region down to the marshes of southwest Georgia, the Flint River has been at the heart of Georgia communities for generations. The 350-mile-long river has provided cultural significance, farmland and irrigation, all while sustaining one of the most biodiverse freshwater ecosystems in the Southeast.

Federal funding for the Flint River has been increasingly uncertain following the loss of over $65 million in federal grants. Gordon Rogers, the executive director of the Flint River Keeper, noted that while federal payroll support has helped the nonprofit in the past, recent conservation suggests that the funding has been inconsistent.

“In recent years, the only federal money that Flint Riverkeeper has received is [Paycheck Protection Program] and payroll-tax-credit grants,” Rogers said. “They were appreciated and not interrupted by the current unpleasantness in D.C.”

Rogers said federal dollars have flowed more freely toward infrastructure repair across the region, particularly sewer separation projects critical to water quality. Federal funds are being allocated for infrastructure repair in the lower Flint River area.

“There has been a lot of federal money spent in recent years, and currently underway, on infrastructure-improvement and repair grants [for our interests, sewers] all over the basin, towns both large and small,” Rogers said. “A particularly important example is Albany, where well over $100 million in federal funds has been spent on the separation of the storm sewers and regular waste sewers, a long-needed project critical to the health of the lower Flint. Smaller-town examples include Buena Vista and Thomaston.”

Rogers explains how these projects aim to improve the river’s health by providing a stable water supply for agriculture and protecting endangered species.

“Two, very large flow-restoration projects in the lower Flint are funded in the main by federal monies,” Rogers said. “GA-FIT, which had COVID (ARPA) funds sent to Georgia and allocated by Governor Kemp to this work. The project seeks to provide resilience to ag-water [irrigation] supply, stabilize low [drought] flows in tributaries of the Flint (Spring Creek, Ichawaynochaway Creek, Muckalee Creek, Kinchafoonee Creek) and conserve endangered mussel species plus their associated fish assemblages. These dollars arrived in GA well in advance of what President Trump’s team is up to and were not interrupted.”

While GA-FIT has already received federal backing, Skywater, a project aimed at maintaining low drought flows on the east of the Flint River, remains stalled as it awaits its final approval from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“This project is funded by federal grants via the Farm Bill through the Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service,” Rogers said. “The final work plan is under review by the NRCS; once approved, there is no telling if the funds will be released or not, and approval itself is not guaranteed. The aim of the project is to restore the drought [low] flows of Radium Springs and other inputs to the Flint on the east side of the river in Dougherty, Worth and other counties. Time will tell on this one. It is the main, and possibly only, water-related federal project currently ‘held up’.”

Advanced Placement Environmental Science teacher, Madeline Oliff believes that pollution harming the Flint could lead to bigger environmental problems. The river consistently faces threats from runoff and sedimentation, which can both harm the water quality and its flow.

“Pollution would be one of the biggest risks, whether that is from agricultural runoff or storm water runoff,” Oliff said. “There are also concerns of sedimentation of the rivers from construction, which can cause an increase in turbidity, essentially suspending soil particles in the river. This can cause a lot of issues, especially with increasing the temperature of the latter as the suspended particles cause the river to become a darker color, this lowers the albedo, meaning more heat from the sun is being absorbed rather than reflected like with clear water.”

Olliff said she believes pollution undermines the rivers’ significance to people, the pollution threatening one of the most diverse freshwater sources in the Southeast.

“In the Southeast, we are blessed to be a biodiverse hotspot for freshwater ecosystems,” Oliff said, “Rivers are the heart of that, as they are home to many different types of fish, amphibians and macroinvertebrates [insects]. Environmental issues like pollution of our freshwater ecosystems are found to have really significant reciprocal effects. Rivers provide some many ecosystem services, such as flood control, crucial habitat for unique species, and cultural significance, as well as the Flint River, which is integral to the Indigenous Americans.”

Community involvement and political pressure are two important factors that determine the future of Flint, according to Oliff.

“One of the most powerful things is activism and education,” Oliff said. “Raising awareness about the issues at hand and being persistent in raising those issues to government offices and positions that can give more funding or change legislation.”

Oliff said she believes protecting the Flint means safeguarding an entire river basin that stretches hundreds of miles

“It is important to remember that it is not just the Flint River itself that is at risk but a whole river basin that consists of over 350 river miles,” Oliff said. “This has far-reaching effects on cities and towns that live in the Piedmont area of Georgia, affecting rural areas of middle and south Georgia.”

Due to the river stretching over 350 miles, the Flint River’s impact of pollution extends beyond its immediate area. It not only affects the people nearby but also multiple ecosystems dependent on the river’s resources.

“The Flint River provides a big source of recreation to the areas, but is also a biodiverse hotspot,” Oliff said. “Recently, a new species of Darter was found endemic to the area. It also feeds into many warm/hot springs down in south Georgia near Albany. The Flint River also serves our agricultural industry and serves to help with hydroelectric power.”

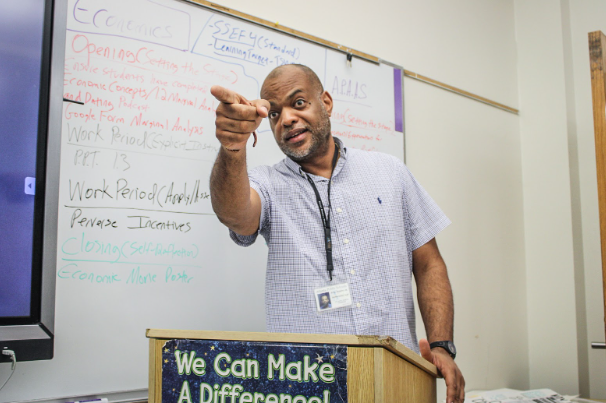

Latin teacher Scott Allen, a close friend of the American Rivers keeper who works with the Flint, tries to spread information on water pollution in his classes. Allen incorporates STEAM-based projects that inform students about the pollution of the Flint River.

“In my Latin I classes, we did a STEAM unit on water,” Allen said. “Basically, where do we get clean water from? How do we clean water? What do we do with wastewater, essentially? While we were doing that, we did some investigating on the Chattahoochee River and all of its tributaries. In fact, there’s one that actually flows through Piedmont Park called Clear Creek. There have been lots of pollution issues over the years.”

Allen emphasized the broader consequences of neglecting the river’s health.

“Personally, I did some research on the Flint River as well,” Allen said. “The Flint River, even though it is this tiny little thing that originates right underneath the Atlanta airport, it becomes a huge flowing river for much of central and South Georgia. It’s critical to everybody’s drinking water down there along the river. It’s also critical for lots of the crops that are grown in our state. So it’s very important for people’s livelihood. It’s not just people’s individual health, but people’s financial livelihood to have a clean river.”

Allen said he believes that inadequate support from the Flint undermines the entire state.

“Any loss of funding to help make it cleaner is just really hurting all Georgians, not just those who live here where the Flint River originates,” Allen said. “But the huge impact is for those who live in Central and South Georgia.”