Katherine Esterl is a senior. She spends her time rehearsing plays, building houses and watching Frasier.

Contact

[email protected]

December 18, 2019

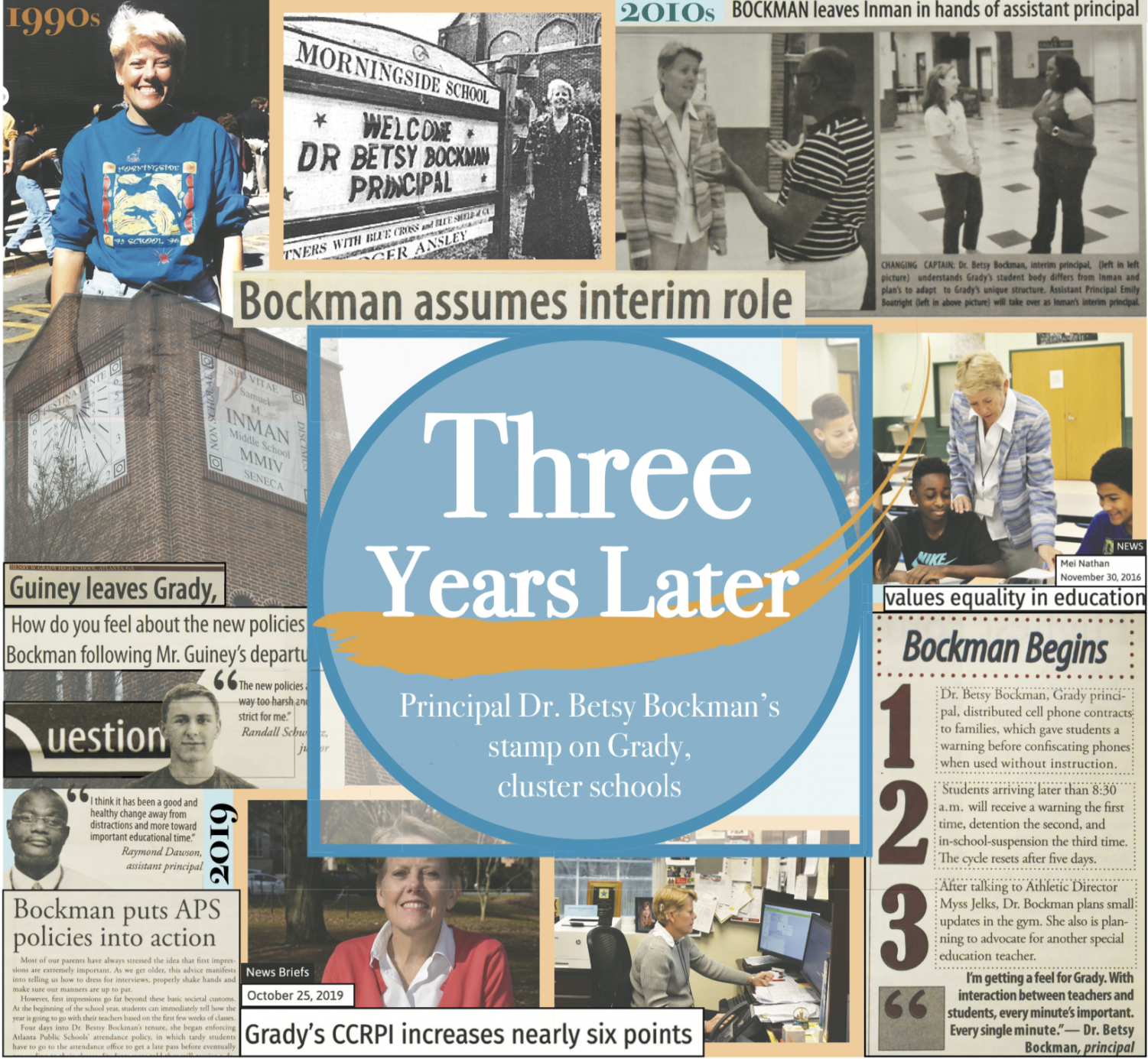

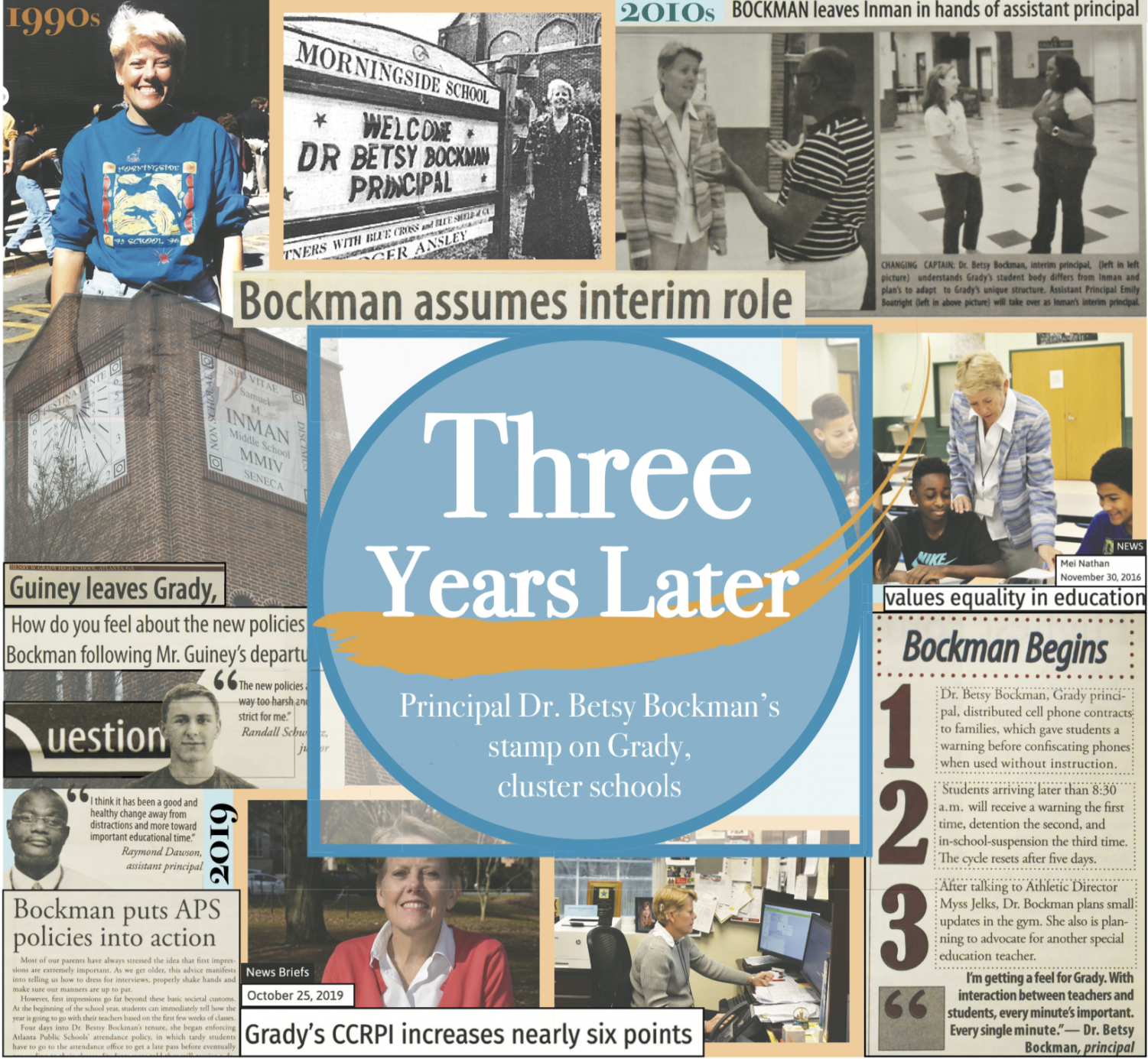

In 2013, she led the biggest gains in student achievement of all traditional Atlanta middle schools. In the years following, she raised test scores at different schools. In 2018, a reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution called her “one of the most respected leaders in Atlanta Public Schools.”

But Dr. Betsy Bockman’s history in education is more complicated than meets the eye.

In September 2016, Grady bid farewell to its principal of two years, Timothy Guiney. Prior to him, Dr. Vincent Murray had held the big job on campus for 23 years. When Dr. Bockman arrived, some teachers were quick to leave, uncomfortable with her changes and “tighten up” attitude.

Dr. Bockman may be known as strict (one teacher said some consider her to “micromanage”), but she says her focus has always been on making school a fair and equitable learning environment for every student, no matter their race, gender or background.

Three years later, Dr. Bockman’s efforts to improve equity at Grady have produced a school much changed since her predecessors left its halls. According to Dr. Bockman and other administrators and teachers, classes are more diverse, scores are up and curriculums are focused.

Dr. Bockman, an Atlanta native and graduate of Northside High School, now North Atlanta High School, was born in 1960. By the late 60s, tensions were high with the growing civil rights, anti-Vietnam and women’s liberation movements, and especially in Atlanta.

Growing up in Garden Hills, her family encouraged activism. Her grandfather supported desegregation, and she attended protest marches with her mother, which taught her to notice “gray areas.”

“It’s really what my whole life has been about,” Dr. Bockman said.

After receiving a Bachelor’s degree from Georgia Southern College in Health and Physical Education and a Master’s from the University of Georgia’s College of Education, she received a Ph.D. from Emory University in urban education.

Dr. Jacqueline Jordan Irvine, Charles Howard Emeritus Professor of Urban Education at Emory, taught Dr. Bockman. She said Dr. Bockman was interested in helping “students who didn’t have strong support systems.”

“Anything you want to know about her commitment and her ability to get along in terms of cross-racial relationships, look at Betsy’s family, and then you don’t have to say very much about it,” Dr. Irvine said.

Dr. Bockman has an adopted family. Three of her children have special education needs, and she is partially deaf and wears a hearing aid, which she said makes her think about kids with difficulties.

“She likes to give people chances,” Dr. Bockman’s son and Grady junior Tomas Bockman said. “She doesn’t like to hold people back.”

Dr. Bockman began her career in education as a physical education teacher and high school coach. She then became principal at Morningside Elementary in 1996, Garden Hills Elementary in 2002, Inman Middle School in 2003, Coan Middle School in 2012, back to Inman in 2014 and finally to Grady in 2016.

Typically, she said, she entered affluent schools that were operating in a disorganized way and worked to tighten them up, emphasizing “bringing people together.”

“I usually come into well-established schools [that] have had good success on test scores, but they could do a lot better, and they could do a lot better for special education and black kids,” Dr. Bockman said.

Abby Martin, Grady cluster parent and former co-president of the Council of Intown Neighborhoods and Schools, said Dr. Bockman “set the foundation of excellence at Morningside” and hired talented teachers.

TACKLING DIFFICULT CONVERSATIONS

But Morningside was and still is a majority white school, and when Dr. Bockman moved to Inman in 2003, she encountered pushback from parents who were concerned about the new implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act. The federal law would increase the number of black students at the school because it allowed students to transfer from poor performing schools to higher-performing campuses.

Martin, who worked with Dr. Bockman personally, said that at one point Grady parents also wished to maintain a white, high socioeconomic class school.

“They were happy kicking out the fragments of our community,” said Martin, who also called some community members “closet racist.”

At Inman, Dr. Bockman openly discussed racial differences. The black and white division was so stark among students, she said, people called the school both “Bankhead and Buckhead,” the former, a predominantly African-American community in northwest Atlanta and home to the former Bankhead Courts public housing project, and the latter, a wealthy white community in north Atlanta.

There, Dr. Bockman noticed that the Gifted, or higher-level classes, had only white students and that black students were failing at greater rates. She shared that observation with her new faculty, even though “no one wanted to hear that,” she said.

“I can’t come in with the assumption that everybody understands that there’s a huge race problem in Atlanta,” Dr. Bockman said. “We have to talk about it because we can normalize it, and then we can move on.”

Her policies included implementing collaborative, project-based learning and limiting the number of Gifted classes students could take, which diversified classes.

AP World History teacher Sara Looman also taught under Dr. Bockman at Inman. Upon arriving, she recalled Dr. Bockman telling teachers, “not all of you are going to like this, and not all of you are going to stay.”

Some students left for private school. Looman thought they might have feared they wouldn’t be in the “good” class, or the white, upper-level class.

Dr. Bockman said she aimed, however, to make every class the “good” class, for all students, regardless of race.

“I want to be able to say I could put my child in every class,” Dr. Bockman said.

Dr. Bockman left Inman for Coan Middle School during the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal, which began in 2009. About 180 employees, including 38 principals, were implicated for helping students cheat on standardized tests, and APS wanted a new class of principals to help the district recover.

She was named APS Interim Executive Director in 2011 and was offered the Coan top job in 2012. Despite being “reluctant” at first, Dr. Bockman said she thought the experience would boost her credibility, proving that she could be successful at an underperforming school. At the time, Coan was a Grady feeder school.

In the beginning, she was not entirely welcomed. Coan students were failing state end-of-year tests, especially in math. Dr. Bockman said she had to “burst [the Coan community’s] bubble.”

“I immediately started changing everything around,” Dr. Bockman said.

She insisted on students wearing uniforms and trained every teacher to teach math so that students could take two math classes a day.

She got involved in classrooms to make sure students were learning the curriculum standards as they were designed. Fighting for improvement, she described her first year as principal there as “war.”

Dr. Bockman said she also experienced difficulties discussing race at Coan. At a 98 percent African-American school, she was a white woman, and with her strict policies, she said some teachers may have seen her as a “threatening force.”

Physics teacher Christie Lowell, who moved to Atlanta from Portland, Oregon with Teach for America, was one of Dr. Bockman’s new hires at Coan.

“A lot of teachers, it seemed, thought she didn’t get it,” Lowell said.

Dr. Irvine said that, disregarding the race factor, the “natural reaction” to change in an organization, including a school, is “suspicion.”

“But that distinguishes good principals from not so good principals—those who are able to, in spite of, and those are the operative words, in spite of the pushback, how effective are they at executing a plan, and it is a major point in raising students’ achievement,” Dr. Irvine said.

Lowell, who later followed Dr. Bockman to Inman, agreed.

“But I think the point of it, of doing what she did, was about ‘anybody can learn, and it doesn’t matter where you came from, and not everybody starts at the same place, and it is about growth; it’s not about black or white,’” Lowell said.

By the end of her first year, Dr. Bockman’s work paid off. Coan students’ Criterion Referenced-Competency Test scores increased by an amount that outpaced the growth of any other traditional middle school in the city. In 2013, 98.9 percent of eighth graders met and/or exceeded standards in reading and 74.1 percent passed math, up from 58.9 percent in 2011.

When she broke the news to her students, they shared tears of joy, she said.

“It was the most emotional thing I have ever been through, seeing red, red, red, red, red, red for years and years and years, and then all of a sudden these kids who had never passed anything, passed,” Dr. Bockman said, referencing the red graph lines that had indicated students’ failure on state-mandated end-of-year tests.

Coan Middle School closed two years after Dr. Bockman arrived due to low enrollment, so in 2014, she returned to Inman Middle School. While there, its College and Career Readiness Performance Index (CCRPI), which considers factors such as state standardized test scores, graduation and attendance, rose from 84.2 points in 2014 to 91.6 points in 2016.

LEADING GRADY

In the fall of 2016, Dr. Bockman moved to Grady, which she said she found disorganized.

“To me, the school was probably 5-to-10 years behind everybody else in following the scope and sequence … it was like they were not part of APS at all, like the curricular aspects,” Dr. Bockman said, sharing her thoughts that some teachers appeared to not follow established curriculum in their content areas.

In response, she intervened in teachers’ planning processes, saying she didn’t want to change “how” teachers taught but “what” they taught. However, some of her work was ill-received.

Former math teacher Jermaine Ross said in an email that after Dr. Bockman arrived, Grady put teachers at the “bottom of the totem pole.” He remembered seeing teachers and assistant principals “literally running” down Charles Allen Drive to avoid being late. He resigned and left Grady in May 2019.

“When I left Grady, it felt like the teaching staff and the administrators were on two different teams,” Ross said in the email. “This was not the culture under the two previous principals.”

Dr. Bockman, however, said her implementation of the tardiness policy, along with other initiatives like the requirement for teachers to post one grade a week, were APS policies, not her own.

“When I came here, the procedures weren’t being followed, so it did seem like I was, like, the bad guy, but Grady often operated very independently of the school system,” Dr. Bockman said. “I think it’s healthier now.”

She also said holding teachers to the same attendance policy as students was “fair.” In the last two years, Grady has consistently had the highest attendance rate of APS high schools.

But just as at Coan and Inman, initial pushback was not unusual for Dr. Bockman, especially for teachers who “don’t like being held accountable,” Martin said.

“If you really aren’t going to be able to be up to the level of proficiency that she would demand in her school, well, you’ll know that pretty quickly, and you probably won’t feel very comfortable being a teacher in her school,” Martin said.

Photography teacher Kimberly Wadsworth said she was “resistant” to Dr. Bockman’s changes at first, explaining that Dr. Bockman presented a “different type of personality that [teachers] weren’t used to.” But today she finds that even the strict tardiness rule has been a good change, helping to keep her organized.

“As much as we’ve [teachers] adjusted to her, she’s also adjusted to us,” Wadsworth said. “She’s not made of stone.”

Others have praised Dr. Bockman for her work to increase diversity in classes. As she and other administrators noticed, honors classes were often a segregational middle step between on-level and AP classes. The honors curriculum for many courses was no different than the work required for on-level courses, but honors classes were majority white.

“To go to these on-level classes now, it does not look like this dumping ground of under-achieving scholars; so, she was right,” said Assistant Principal Willie Vincent, who does scheduling and worked closely with Dr. Bockman on her effort.

She has dissolved almost all honors classes. Today, honors physics is the last remaining honors class for which there is also an AP course.

Dr. Bockman also changed the way in which students were selected for higher-level classes. In the past, selections depended on teacher recommendations, which were subjective and often favored white students, even if those students performed worse academically than black students.

Now, Vincent recognizes students with potential based on their PSAT scores and grades. Students with below an 85 in their previous course are not necessarily recommended for an AP class.

“Dr. Bockman is a believer that nothing should be arbitrary. Everything should be defensible,” Vincent said. “It should be concrete, and I should be able to stand up in front of the world and say how this process works.”

Dr. Bockman also encouraged previously started efforts to diversify AP classes, which are often composed of more white students. Vincent and Assistant Principal Tekeshia Hollis had worked to encourage specific students to take AP, even for those who “fly under the radar.”

“When Dr. Bockman came, of course she just challenged us even more to find ways to eliminate loopholes,” Hollis said.

Since Dr. Bockman’s arrival, the number of students taking AP has doubled as a result of new courses like AP Human Geography for 9th graders and AP Seminar and Research. She said AP Seminar is one of Grady’s most diverse AP classes.

And this year, Grady’s CCRPI, which considers AP enrollment, rose almost six points, to 87.5 up from 81.7 in 2018, the highest in the school district.

State mandated end-of-year Milestones test scores also increased. Proficiency in English and Language Arts has grown from 56 percent in 2016 to 72 percent, and proficiency in math rose from 37 percent to 54 percent in the same time.

In the past two years, Grady’s graduation rate has been above 90 percent.

Wadsworth said Dr. Bockman has a “big heart” and “genuinely cares” about kids and education. Tomas Bockman said Dr. Bockman “tries to take care of people.” This year she bought a pair of basketball shoes for a Grady basketball player and helped a family celebrate the holidays.

“She went by the grocery store and bought, like, a whole Thanksgiving dinner for one of the families here at Grady,” Tomas Bockman said.

Superintendent Dr. Meria Carstarphen remembers running by the Grady field during Inman’s football practice. She said Dr. Bockman and her family were in the stands in support of the athletes.

“You can count on Dr. Bockman to be at not only athletic events but theatrical and musical performances, debates,” Dr. Carstarphen said.

Dr. Bockman thinks there is still work to be done, and she passes that message to teachers. She occasionally emails them articles about how to enforce equity in education.

“She pushes hard on that, and it can be really exhausting sometimes because you’re like ‘What else can I be doing?’” said Looman. “But she asks that question. What else can we do? You know, we’re not done.”

With reporting by Charlotte Spears

Katherine Esterl is a senior. She spends her time rehearsing plays, building houses and watching Frasier.

Contact

[email protected]

Debbie Mobley • Dec 21, 2019 at 8:13 am

Excellent balanced article – good stuff!