According to public records attained through APS, there was one reported incident of sexual misconduct at Grady, in this case sexual battery, within the past three school years. However, multiple students shared personal accounts of sexual harassment and assault that occurred during that period, suggesting a discrepancy between the number of incidents that take place and those that are reported.

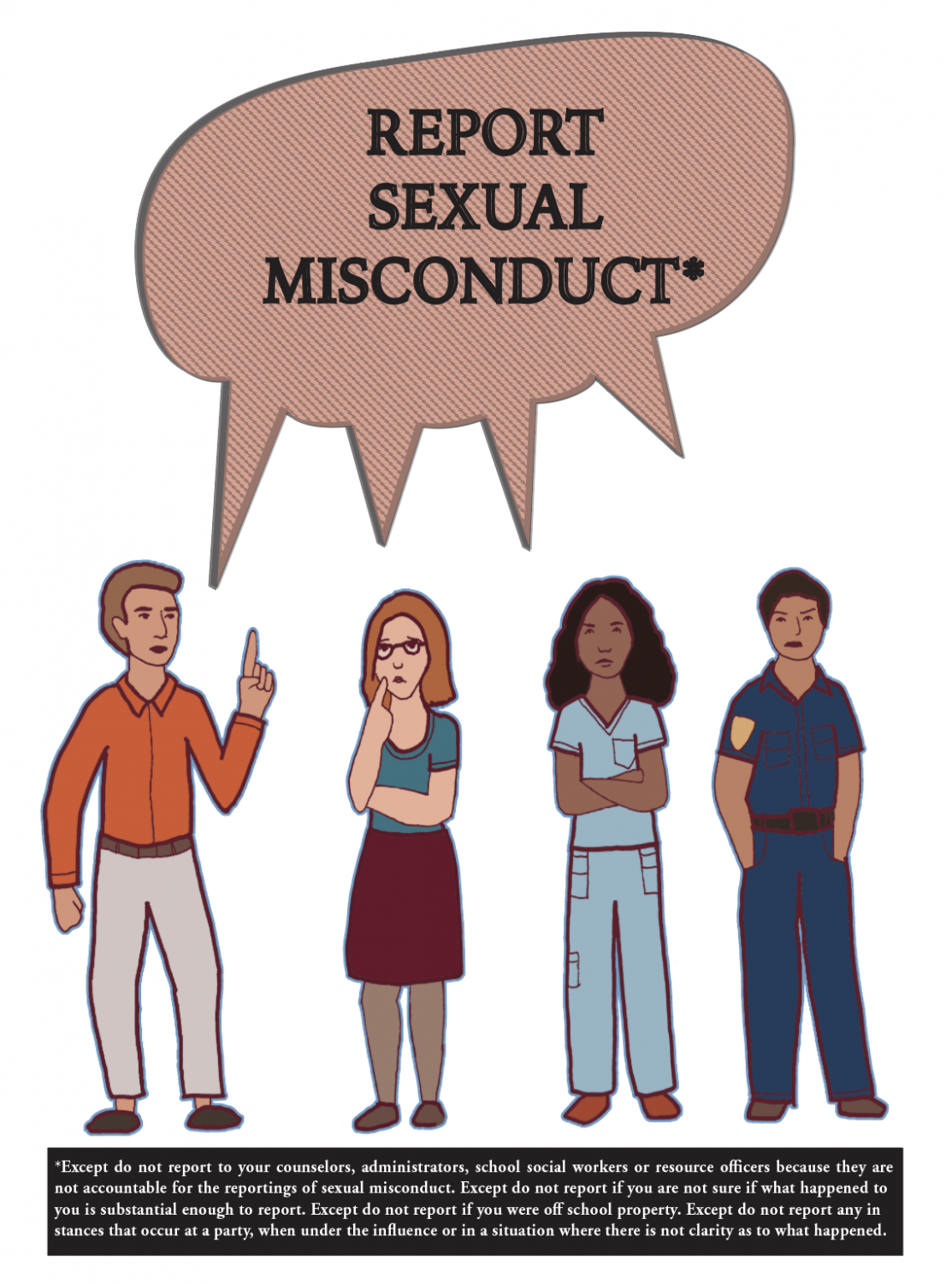

Many students are unaware of the steps they should take to report an incident of sexual harassment or sexual assault.

“I was honestly thinking … ‘Who do we go to? Where do we go?’” said junior Evelyn Robertson, a victim of sexual battery who was groped while walking to class. “Luckily Mr. Howard was still outside. I would’ve probably gone to the Office of Student Affairs or the Counselor’s Office, but I think it would be good to tell students ‘Hey if this ever happens to you, this is where you should go.”

Robertson was satisfied with how her situation was handled. Assistant principal Rodney Howard pulled up camera footage. It was too blurry to make out any faces, so he told Robertson to come to him if she ever recognized the perpetrator in the hall.

But still, there is a sentiment that the reporting process is unclear.

Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman said that if a Grady staff member knows about an instance of sexual harassment or assault, it is their responsibility to report it to an administrator, a fact also outlined in Georgia Department of Education law. They should record as much information about the situation as possible, including, for instance, details of what happened, the time, present witnesses and the name of the alleged perpetrator.

However, after the Southerner talked to multiple administrators and faculty members, it was difficult to pinpoint a clear chain of command. The counselors, to whom some students made reports, declined comment, despite the fact that an administrator referred them as responsible for handling accounts of harassment and assault.

The school resource officer and social worker also have responsibilities in dealing with incidents. However, while one of the school resource officers said he hadn’t received any reports in the last three years, the social worker, who also works at Springdale Park Elementary, said she had received three.

“Every situation is different, but it is our responsibility to investigate an allegation or a claim,” Dr. Bockman said. “I’m not sure why people would pass that on because it is our [responsibility] to investigate sexual harassment and assault.”

When Ellen was harassed on campus by the friends of the boy she was dating, she went to her counselor. After being told she could do nothing if she didn’t want to press charges, she received no further help and did not feel inclined to go back after later encountering more harassment.

Amy was told the same thing. Since her experience occurred off campus, the school could do even less. However, according to Dr. Bockman, past instances of off campus assault and harassment have resulted in students receiving emotional support and even being separated from each other in class.

“If the victim reports that to us, we can refer the student for outside counseling,” Dr. Bockman said. “We have an organization, Pathways, that comes to school. We can do that. Our counselors can provide support as well, work with the parents to find support.”

However, since Amy did not receive such help, she also neglected to return to her counselor for later incidents.

“I was left feeling angry, I guess, sort of just that feeling that you get of why is something so unfair, but you know you can’t change that,” Amy said.

Amy is not alone in her frustration. Another student, *Maria, brought evidence to the administration about sexual harassment occurring against her during her freshman year through text messages and screenshots from a then-senior boy. The text messages were meant to objectify Maria in a sexual nature, something she had not consented to and was not comfortable with.

“They wouldn’t even address [the messages] as sexual harassment,” Maria said. “Even despite what I had told them about events that had gone on throughout the school.”

Despite the confusion regarding the school’s handling of instances of sexual harassment or sexual assault, the process is outlined in the Atlanta School Board Policy Manual in code JCAC. According to Georgia State Law, schools and other places of education and care are required to report incidents no later than 24 hours “from the time there is reasonable cause to believe that suspected abuse has occurred.”

Failure to report timely classifies as a misdemeanor. If a student reports harassment or assault, the faculty member who receives the complaint must immediately notify an assistant principal or the principal, and an investigation must be conducted for all allegations brought to their attention.

Depending on what the investigation yields, it is then up to the administrators to use the levels of discipline established in the APS handbook as a guideline to decide what disciplinary actions will be taken. Since these incidents tend to differ case by case, it is ultimately up to the administrator’s discretion.

These disciplinary actions range in severity and include local interventions, in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension and the most extreme measure, reassignment to another school. If the case is deemed too serious for the school’s administration, it is passed on to the Office of Internal Resolution for a more in-depth investigation.

While the school only has jurisdiction over what happens on school property or during school-sponsored events, students often bring their personal lives to school, which creates a gray area.

“The only jurisdiction the school would have would be something that happens on the weekend if it is a major felony that has taken place or a student has been arrested or charged with a felony, or if it is an instance of cyberbullying,” said Dr. Shannon Hervey, APS Coordinator of Student Discipline. “Other than these things, if a student is sexually harassed by another student on the weekend, and is at a park or random party, then their administrator could not discipline that student for that.”

While Title IX and state education policy have specific laws that apply to sexual harassment, they also protect students from discrimination and promote their well-being. Off campus incidents can hinder students’ ability to learn if they feel uncomfortable at school, raising the question of how limited the school’s power should be. An exception has already been made for cyberbullying, which the school has jurisdiction over despite occurring off campus.

According to health education consultant Justine Fonte, sexual harassment and assault that occurs out of school can have long term effects on students, and therefore schools should play a role in addressing these incidents.

“Because so much of social life and school life are almost synonymous in terms of networks, I think it’s important that you are addressing the issues that are happening throughout one’s day,” Fonte said.

Victims of sexual harassment sometimes feel that the severity of what happened to them doesn’t warrant administrative action, so they don’t come forward. A sophomore, *Sarah, has had classmates whistle and make inappropriate comments toward her in the halls. While this irritates her, she feels it doesn’t warrant reporting.

“I feel like not much would happen with that because it’s not considered extreme … so it’s just not worth it,” Sarah said.