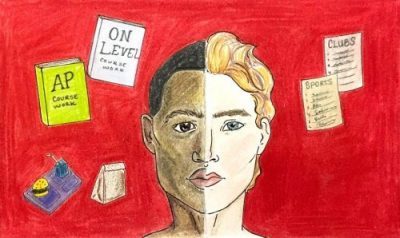

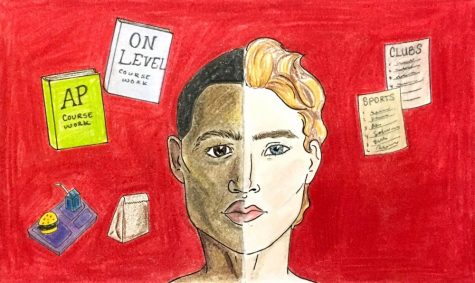

Individually we are different; Together we are divided

September 8, 2017

By Alex Durham and Katie Earles

“Individually we are different, Together we are Grady.” This motto has represented Grady since the 1990’s, but looking from the classroom to where students decide to sit at a pep rally to after-school activities, there are glaring racial divisions that contradict the phrase.

“People of different races do not sit together [at lunch]; they’re on different sports teams and in different clubs,” said senior Aaron Burras, Student Government Association president, who is African American. “I have a black friend who wants more white friends but is afraid to come talk to my white friends. People are scared to branch out from the people they become friends with in elementary school because why get away from comfortable when comfortable feels so good?”

The roots of these divisions are the neighborhoods students grew up in, which was ultimately decided upon by the socioeconomic status of the families. The friend groups that children develop in elementary school influence the people they befriend at the high school level, so the racial division seen in Grady originated when district lines were drawn decades ago.

“Further divides can be seen once testing for Gifted in elementary school begins,” Grady Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman said. “[The divide] gets worse through the math and foreign language tracks, which we can see at Grady.”

For related sidebar commentary and Letter to the Editor, please see:

https://thesoutherneronline.com/64394/comment/campus-appears-segregated-through-eyes-of-a-newcomer/

Elementary Schools

In 1872, Atlanta was divided into two parts: the affluent white community living north of Ponce DeLeon Avenue in areas like Virginia-Highland and Ansley Park, and the largely impoverished African-American community living south of Ponce, according to Kennesaw State history professor LeeAnn Lands.

This line split the community in two, and the line still exists today. Atlanta school board member and 2006 Grady graduate Matt Westmoreland witnessed the divide.

“The most vivid memory I had [of the racial divide] was in AP Lit in Mr. (Lawrence) McCurdy’s class,” Westmoreland said. “I would walk into class and see 15 or 16 students, almost all of whom were white, all of whom had grown up in the Morningside, Ansley Park, Sherwood Forest or Virginia-Highland area, and next door, down the hallway, was a 9th grade non-honors Lit class that had twice as many kids in it, and everybody was black.”

If these divisions were seen as prominently in the Grady of 2006, where do they truly begin?

Located between the Virginia-Highland and Ansley Park neighborhoods, Morningside Elementary School is a largely affluent school that is known for its academic rigor. Students are learning about race relations through their core classes.

“To these kids, history seems so, so old,” said Jennifer Moore, Morningside challenge teacher. “The Civil War and the Civil Rights events in the 60’s are basically the same distance away to them.”

Although the school is primarily white, there are underlying cultural divisions between races.

“Some families are all in, 100 percent, about diversity and acceptance, but if you go a few levels deeper with some who claim they are open to branching, it’s like, ‘Fine I accept it, but I’m not gonna invite you over to my house for dinner,’” Moore said.

According to a PBS story covering discussions on racism, young children inherently learn from those around them. This trait enables kids to form thoughts on race relations through the interactions with those around them.

“A lot of these kids have babysitters or nannies who are of another race, and when you have an in-home caregiver that you’ve really bonded with, you’re moving [toward accepting diversity] already,” Moore said.

Similar to Morningside, the Springdale Park Elementary district is comprised of primarily affluent neighborhoods where many parents are able to assist their children with schoolwork.

“Between me, my husband and babysitter, we pretty much go through their homework with them every day,” said Stephanie Libby, mother of Gus (1st grade) and Leo (preschool). “We’re pretty involved. My husband does flashcards with the kids before school, and I volunteered at Leo’s preschool every Friday morning for a couple months until he got comfortable with it.”

“I feel like my kids have a pretty diverse group of friends, said Jessica Boatright, mother of two at Mary Lin Elementary. “[This diverse friend group] has been true through preschool and elementary school with Mary Lin.”

Not only do friend groups seem inclusive and diverse, Mary Lin offers an after-school program for students with working parents.

“My husband and I work full time, so my kids go to the after-school program where they can get homework help,” Boatright said.

Steps are being taken to inform students about race relations at an early age.

“Every teacher they have had has spent time getting the children to think about and celebrate their differences and respect each other, whether it’s a difference of religion or race or cultural background,” Boatright said. “It’s not only part of their everyday experience, it’s intentional on the part of the school as well.”

Hope-Hill Elementary is the only primarily African-American school that feeds into Inman Middle School, which feeds into Grady. To increase diversity within the school, Hope-Hill hosts several social and academic events to help students and their parents get more involved in the school community.

“I think fueling more things like events and activities that force that kind of integration [would help improve interaction],” said Gifted Writing teacher Alicia Goodman. “For example, we have school dances, back-to-school drives, we have those things to force our parents to mingle with each other.”

With the school’s predominantly African-American population comes the stereotype that Hope-Hill students are less well-behaved than the other elementary school students when they move on to the integrated Inman Middle School.

“Out of all the clusters, [people] feel Hope-Hill is worse because we have more of the African-American population,” said school counselor Kimberly Miles. “When the students get to Inman, they feel out of place and as if they don’t belong there.

“I grew up in a mostly black neighborhood, Hope-Hill, and then when I got to Inman, it was weird because it was a different race, so I just stayed talking to black people,” sophomore Zacaria Williams said. “They [Hope-Hill staff] told us there was going to be a lot of different faces and different people out there, and that it was going to be a gradual thing over time, but that we’ll eventually get used to it, like I did. I have a variety of different races of friends now.”

Inman Middle School

Inman Middle School is located in the Virginia-Highland neighborhood and near Ponce de Leon Avenue. Receiving students from elementary schools such as Hope-Hill, Centennial Place, Morningside, Springdale Park and Mary Lin, Inman is a school used to diversity.

“It starts with the housing patterns and the affluence; the more money you have, the more choices you have,” said Dr Bockman, who is also Inman’s former principal. “The Gifted Program and the advanced math program impacts this division; those in these programs are mostly white — based off of experience and exposure. The choice of electives also, unintentionally, I think, segregates.”

The division seen in Grady is evident to teachers in Inman classrooms and extracurriculars as well. Since she started teaching at Inman in 2006, eighth grade math teacher Donna Jackson-Howson noticed the division has been stark between the accelerated math classes and on-level math classes she teaches.

“The on-level math classes were primarily black, and the accelerated classes were primarily white,” said Jackson-Howson. “You have parents trying to get their white kids into those accelerated classes because they think it’s something big, and you can’t tell the parents their kid is struggling in accelerated and probably shouldn’t be in the class because, to them, that doesn’t make sense.”

While these divisions may be apparent to teachers and administrators, students do not seem to see the division in their classes or extra-curriculars.

“I haven’t seen that much [division] at Inman while I’ve been here,” said Brandon Buxton, an African-American eighth grader. “Most of my classes are well-mixed, and I get to be with kids that are different races than me.”

The division in math classes seems to be improving as Inman recently eliminated the advanced math track, leaving just the on-level and accelerated math courses.

“This is the first year where I have these nice classes where I see black and white faces together,” Jackson-Howson said. “I have all these kids with different math abilities, and that means I have integrated classes.

Grady High School

Grady becomes the mixing pot for these students when they get to high school, and that is where students begin to see a noticeable divide; this is a divide seen in classes, extracurriculars and even social events.

“Academically, there is definitely a big separation,” senior Isaiha Davis said. “In my AP Psych class, it’s like 75 percent white and 25 black, and this split I can see more across math and language arts classes. In standard precalculus, I’m the only white guy, but in Honors British Lit, there are practically only white people.”

This separation is seen in sports as well, with divisions between track and cross country and football and ultimate frisbee.

“I’m one of [five] white guys on track and [there are three] black guys on cross country,” Davis said. “When I played football, I was one of the only white guys. Stereotypes are mainly the reason why they are like this. No one is likely to go into a sport that they aren’t stereotyped to go into.”

Students’ friend groups are divided, too — stemming largely from the neighborhood they grew up in.

“I feel like kids, they choose to be around what they see in their neighborhoods, what they see when they go home, who they grow up around,” Grady senior Amir Crowe said. “I know that’s what I did in elementary school. It wasn’t something we noticed at the time, it was just what we were comfortable with.”

Classrooms are one of the areas at Grady that are most prone to racial divides. According to school data, Grady is 47 percent African American and 39 percent white, yet white students are the majority in 23 of the 25 Advanced Placement (AP) classes.

“I see the divide in some of my classes, but definitely in the AP classes,” Crowe said. “If you look at the racial statistics in those classes, then going down to honors classes to see who’s in what class, there is definitely a racial divide.”

The talk of racial division is not new, either.

“We’re having the same discussion we had seven years ago, the same discussion we had 20 years ago, and the same discussion I’m sure they had in the 1950’s,” said Mario Herrera, English teacher and debate team coach.

Self-segregation at Grady is evident, even to Grady’s newest students in the freshmen class.

“I think self-segregation is a problem because if you’re always in your own little groups, you’re going to create negative or positive impacts on those groups,” freshman Trinity Lewis said. “Just by being in the same groups, the groups that only think like you and only look like you, there is a problem.”

“When I was younger, I grew up in a white neighborhood, and I didn’t start hanging out with my color kids until about seventh grade,’’ said freshman Lashon`taneise Butler. “I didn’t know how they were going to react to me because I act white; I talk like a white person. Then I got to eigth grade at Inman, and let’s just say the black side of me just came out. I would actually talk very, very proper, and I would pronounce all of my words. My nickname that my family called me was ‘white girl.’ It would be like `Shonty, why you always act so white?’ and I would just say I grew up around white people.”

Self segregation aside, Grady also is not immune to racism. On Aug. 25, a screenshot of texts between two juniors went viral on social media. In the texts, one girl used a racial epithet to refer to another girl’s African-American boyfriend. The other girl called him “an abomination.”

“I think this is conversation opportunity,” Dr. Bockman said of the incident. “We’re prepared if students want to talk about it. I think it was just … hurtful, and it says more about that person. It doesn’t represent Grady; it represents small-mindedness of somebody at a certain point in time.”

In terms of bridging these divides, school board member Westmoreland had several ideas stemming from his time as a student and, now, an outside observer on the board, which sets school district policy.

“In terms of making clubs and other extracurriculars more diverse, students need to be inclusive and make a conscious effort to making a welcoming, warm environment when they get there,” Westmoreland said. “I had lunch at the same place every day — in the Southerner room or on the top of the hill. Go to the bottom of the hill. Sit in the cafeteria. If there’s a divide, tear down the wall.”

-With reporting by Rachel Price

Related Letter to the Editor: